BREAKING

BARRIERS

Quarterly Report

November 2022

Meet young people where they are: how to turn optimism into opportunity

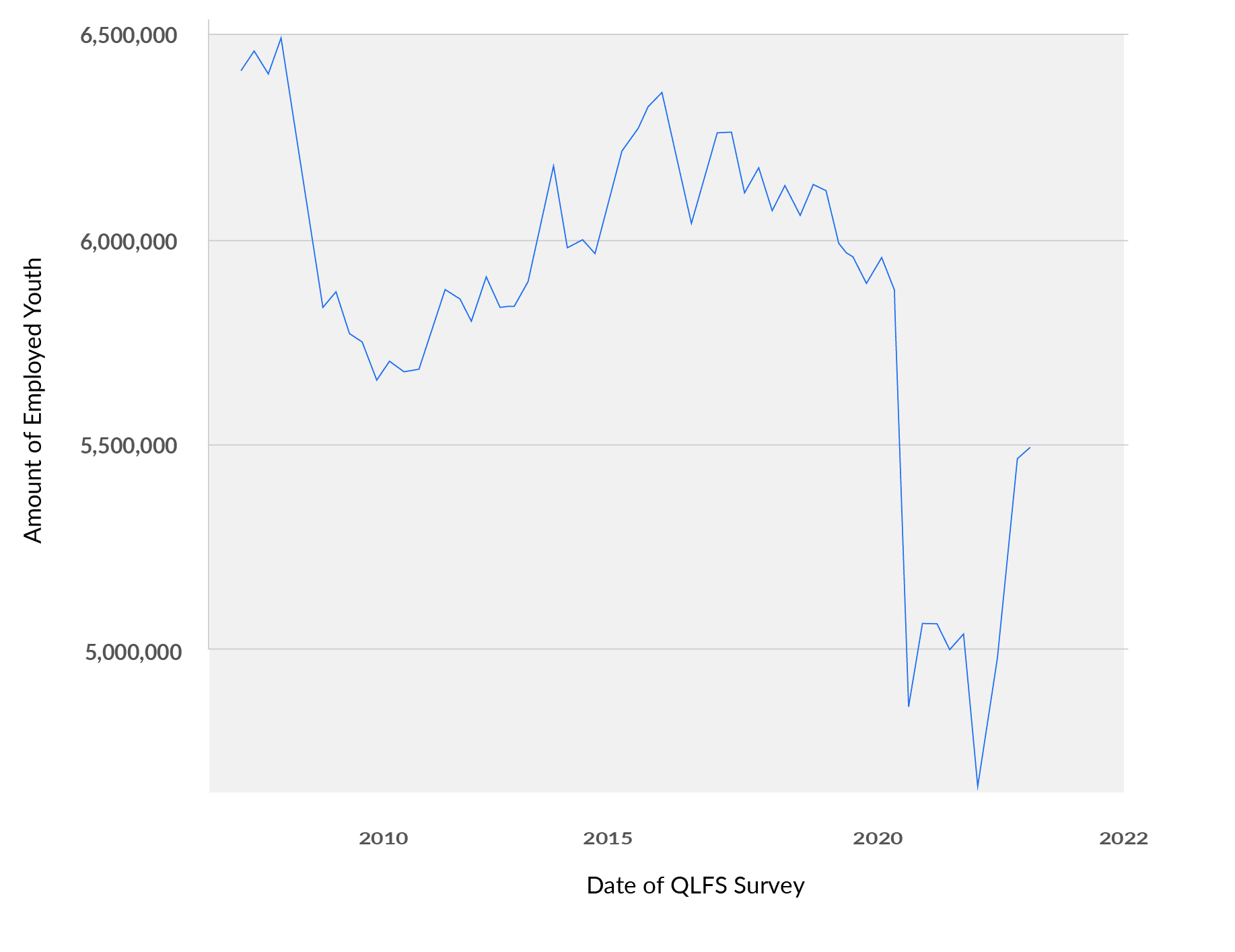

Despite slight upticks in employment—due to growth in employment in construction, transport and community and social services, the third quarter of QLFS 2022 results continue to show that the youth remain vulnerable in the labour market with an unemployment rate of 45.5%. QLFS data from the last few quarters continues to show that there are more young people working in the informal sector than there were pre-COVID (QLFS, 2022), but that the current rate of job growth in the informal economy is still insufficient to compensate for job losses in the informal economy. However, this shift creates an opportunity, but to seize it, we need to understand what drives it.

The economic inclusion barometer, a composite index developed by the Motsepe Foundation, is an attempt to both quantify and qualify exclusion in South Africa on six dimensions—and the results reinforce what we know to be true. Exclusion in South Africa is unsustainable and poses a significant risk to the economic and social stability of the region. And yet, young people’s optimism and resilience remains undimmed. According to the Afrobarometer data from 2021, young people, more than any other age group, are least disenchanted by the future—despite all data to the contrary. Their optimism and resilience propels them to seek opportunity wherever they can–increasingly in the informal economy, finding a way to make money in micro-enterprise and small-scale hustles. This “small picture” optimism–the ability to keep looking for opportunity and bounce back after disappointment–is fueling earning even where jobs are scarce.

If society’s most excluded are still hopeful, surely we can do better than having them shoulder the burden of optimism alone. We must work with them to turn all their efforts at earning into stable sources of income and pathways into employment. By paying close attention to where young people are directing their efforts, and what barriers they encounter, we are learning how to meet them where they are.

KEY INSIGHTS FOR

THIS QUARTER

INSIGHT 1

More young people are hustling now than they were pre-COVID. We need to meet them where they are–with relatable content, inclusive procurement, and a language that recognises their work and worth.

The QLFS suggests that more young people (~1.2 million, according to QLFS) are hustling than they were pre-COVID. To make sure these hustles are supported and are sustainable, Harambee decided to design content to support these efforts, and make them more sustainable and less precarious. To support young hustle-preneurs, we first needed to use platforms and formats that they prefer–we needed to meet them where they are. In the past, Harambee offered written content on its mobi-site, but the team producing it noticed that repeat visits were low. Investigation of engagement drivers showed the clear generational shift in preference, towards audio and visual content of shorter formats–no longer than 3 minutes.

We developed a new kind of delivery format in partnership with community-based organisations like Afrika Tikkun: a podcast series called Bozza Moves (Boss Moves). It profiles five young South Africans like Octoria, a 24-year old entrepreneur from Pretoria, who cites “empty pockets” as the inspiration to start his sneaker cleaning business. His podcast lessons include checking that there is demand for your business, following up on customer payments, and managing spending. These episodes were piloted with a group of young South Africans who had completed working as part of the National Youth Service, via push WhatsApp messages. The results show quantitatively higher levels of engagement with the content, and clear interest and enjoyment. More pilots will follow, including TikTok style videos. Other content includes “Level Up” a series of highly engaging, short videos with clear lessons and a focus on outcomes, as well as “Biz Chats with Xoli” – an “agony aunt” for young micro-entrepreneurs, answering their questions to enable them to start and stay hustling.

Also, youth-led enterprises have very specific needs. They are small,informal, community-driven, and struggle to access existing funding. ECD (early childhood development) has been identified as an area of growth for youth-led businesses by the Presidential Youth Employment Intervention. However, in this sector, 40% of early learning programmes are registered or conditionally registered, and even among those that are, 25% don’t have access to the ECD subsidy—a major source of funding. Few micro-enterprises–in any sector–have the financial processes, human capital and infrastructure necessary to meet the registration requirements that would enable them to access the subsidy, nor the visibility that would unlock considerable social and private investment interest. Meeting micro-enterprises where they are means providing targeted registration readiness and process assistance, inclusive skill development opportunities and access to financial tools such as microloans, financial record-keeping, saving schemes and rent-to-buy infrastructure. Procurement aggregation–allowing multiple SMMEs to aggregate and bid for procurement opportunities that would have otherwise been out of reach, is a vital solution advocated in Gauteng’s recently passed Township Economic Development Act (TEDA). The Act, signed into law this year. Others include developing taxi ranks–hubs of informal activity–into micro-central business districts and to support the taxi economy to scale and grow supporting value chains. Meeting youth led and township businesses with registration support, accessible financial support, and targeted procurement can go a long way towards inclusion.

And finally, we need to recognise the non-linear nature of the earning journeys of young people. They churn between short-term formal jobs, piecework, hustling and doing unpaid work to meet a need in their community—all of which develop relevant skills, but as a society we have inadequate language and mental models to describe how these experiences add up. A new, shared skills framework, based on globally relevant, cutting-edge frameworks such as the ESCO framework (European Skills Competencies and Occupations) is premised on the nature of unemployment and the future of work. Customizing this framework for the South African context can help us break down all kinds of work experiences into component tasks and knowledge—like customer service skills gained from micro-enterprise, or diary management from childcare— that transfer across sectors and into formal contexts. Developing this unified language can enable the whole ecosystem to support young people to make career paths out of the actual opportunities in front of them.

Figure 1: Meeting youth led businesses with accessible support resources can go a long way towards inclusion

INSIGHT 2

Inadequate access to affordable data and the internet still hinders job seeking. We need cheaper data, and greater access to connectivity. And this also creates jobs.

Fewer than 10% of South Africa’s population has internet access at home. Male-headed households are twice as likely to have internet at home, and white-headed households are fourteen times as likely to have internet at home, and young people across the board–less likely to have internet access at home (General Household Survey, 2021). Harambee’s community partner organisations continue to identify data and connectivity as a barrier to application rates in more rural areas. At first, data costs were presumed to be the main barrier–but digging deeper, it was clear that consistent connectivity itself was the problem. Harambee chose to meet young people where they are–designing a makeshift offline registration process that used a call-in option, allowing Harambee contact centre agents to apply on behalf of work-seekers.

But, the digital data and connectivity divide remains a jail sentence that is handed down repeatedly through the generations. But, it can also shed light on areas for investment. Both the government and the private sector can drive specific investments to stimulate greater economic mobility, such as innovating and scaling financial products to serve the least banked, or to provide cheap data and connectivity in the least connected areas. This allows young people to not have to make a choice between traveling and buying data for work-seeking vs putting food on the table.

Harambee’s partnership with Operation Vulindlela has helped accelerate solutions to the barrier of expensive data and poor internet connectivity. This partnership has been able to draft and publicly gazette a set of standardized municipal by-laws for deployment of electronic communications facilities, moving us closer towards the goal of increased connectivity for all. Further, to increase the commercial viability of deploying broadband infrastructure in low-income communities we have advanced a partnership with the Presidency and the Department of Communications and Digital Technologies to design a Broadband Access Fund, that will provide incentives to private operators to enable broadband access to 14 million homes in low-income areas that are otherwise not commercially viable. This effort makes inclusion a focal design point of connection–with the goal of bringing jobs to more places by enabling remote work via connectivity.

There are many other examples where the private sector partnerships have driven towards concrete and collective action. For example – Merchants, a leading outsourcing service provider, recently launched a state-of-the-art contact centre in Soweto, bringing hundreds of new, stable, high-paying contact centre jobs into the township. Located behind the Jabulani Mall, this facility will result in job creation and enterprise development for young people. The partnership’s key focus is to increase employment and skills development as a direct response to the country’s youth unemployment challenge.By reducing data costs, increasing connectivity, and bringing connectivity AND new jobs to young people, we can meet them where they are–and increase both productivity and employment as a result.

Figure 2: Reduced data costs and increased connectivity can increase both productivity and employment for youth

INSIGHT 3

Young people need opportunities where they live. Public employment programmes work, particularly for our most excluded.

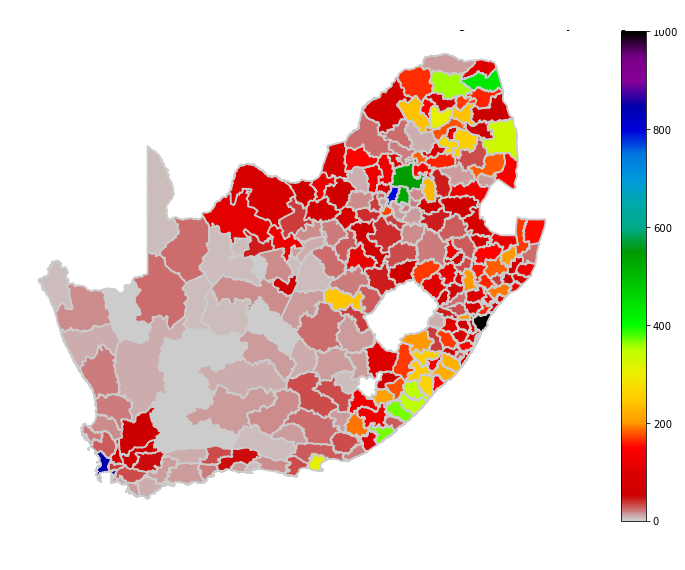

For most young people, the greatest dimension of their exclusion is geographic or demographic. If we are to bridge the gap between informal earning and more structured employment, we must bring opportunity to their door. The Department for Basic Education school assistant programme, unique in its reach and scale in South African history, shows a clear role for public employment programmes in this. And this was evident in the latest QLFS data–community and social services posted an uptick in Q3 jobs for youth.

Data from the third wave reveal how the DBE programme activates and engages a unique cohort of economically underrepresented young people, across every area of the country, including those where virtually no other jobs are available. Notably, the cohort of work seekers who joined SAYouth because of the DBE programme (versus the cohort that joined during the rest of the year) faces higher employment barriers on average: they represent a higher percentage of work seekers from poorly resourced schools (quintile 1-3 schools), which is a proxy for access to resources in general; they were more representative of women; they were twice as likely to come from rural areas and provinces with higher youth unemployment. This cohort is also slightly older—possibly representing the re-engagement of work seekers who had become discouraged beforehand and pointing to the potential of such programmes not just to harness optimism, but also to reignite it.

As the fourth wave of the DBE programme gets under way, we are following the exit paths and outcomes for earlier waves and learning how to help them build bridges into self-supported earning. This is vital, so that their newfound confidence is not squandered in stranded skills. Meeting them where they are across the ecosystem—with recognition, with micro-enterprise support in ECD and agriculture, and with connectivity that opens remote work opportunities in the formal sector—is critical.

If we focus all our attention on “jobs” versus earning, we risk missing a powerful lever to support young people. Instead of pulling against the direction of their own efforts we can amplify them, putting the structural, geographic and personal support in place to help them make the most of what they are already trying to do.

Our quarterly labour force survey results continue to emphasize the price we all pay—and will continue to pay, with interest—for decades of structural exclusion. But if we act together to meet excluded young people where they are, with insight and targeted support, we can turn an abundance of optimism into true inclusion.

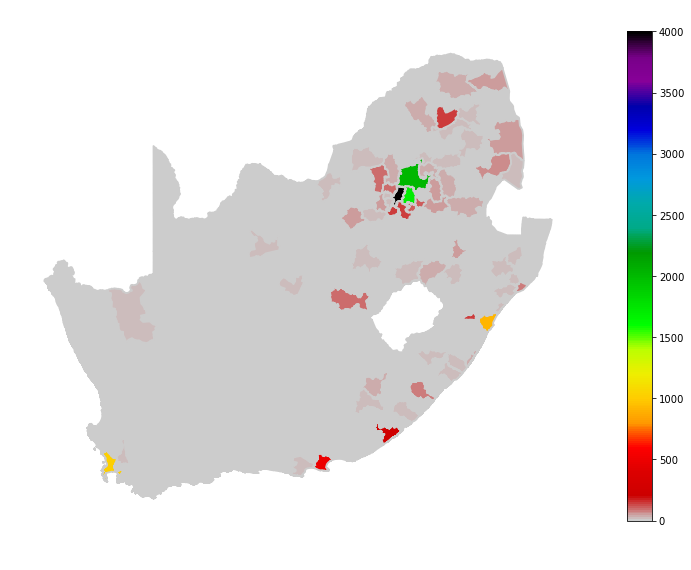

Figure 3: Youth Employment Density by South African Municipality (2020)

*EJ responses for 2020 who reported having a job were overlayed with municipality. Grey indicative of a jobs desert

Figure 4: DBE Teacher Assistant School Locations by South African Municipality (2021)

*DBE data showing the location of schools where teachers assistants were placed per municipality

Youth employment trends

QLFS Q3 2022 reveals similar youth employment levels to last quarter with youth employment figures remaining ±400,000 lower than they were pre-pandemic. Employment for young women has not seen the same recovery as employment for young men, and remains closer to pre-pandemic levels. There is increasing evidence of the ‘temporarisation’ of youth jobs. Youth jobs are disproportionately temporary with the number of permanent jobs, with tenure longer than a year, continuing to decrease this quarter. An industry level analysis of the QLFS Q3 2022 data suggests that much of the post-pandemic recovery comes from the community services sector that now comprises 22% of youth jobs.

Figure 4: Youth employment levels remain lower than they were pre-pandemic

Source: Data from Stats SA QLFS 2022 Quarter 3

NEED MORE INFORMATION?

WANT AN OFFLINE VERSION?

Stay Connected

Stay Connected