SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

Young women and children: first or last? The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young women’s employment.

This Women’s Month, we continue to highlight the barriers and challenges faced by young women in the labour market. The latest QLFS data suggests that unemployment for youth aged 18-34 was approximately 58%, with Black African young women being hardest hit. In a crisis like the COVID pandemic, women and children do not come first—indeed, all evidence suggests that they come last. Indeed, the latest QLFS data suggests that women have been triply-disadvantaged during the pandemic–they have been the most exposed, the least protected, and carry significant additional burdens.

The latest data shows men’s employment in South Africa has returned to pre-pandemic levels, while women’s employment remains 8% lower. The shock to women’s labour force participation during the pandemic has exacerbated the significant barriers young women already faced.

Fortunately, our partners in government, civil society and the private sector have started to recognise and respond to this triple-bind, and there are positive indications amid the dire picture that give us clues for how we can resolve it. Now, more than ever, we need to make sure that young women can survive job loss, then re-enter and stay within the labour market—the theme of this edition of Breaking Barriers.

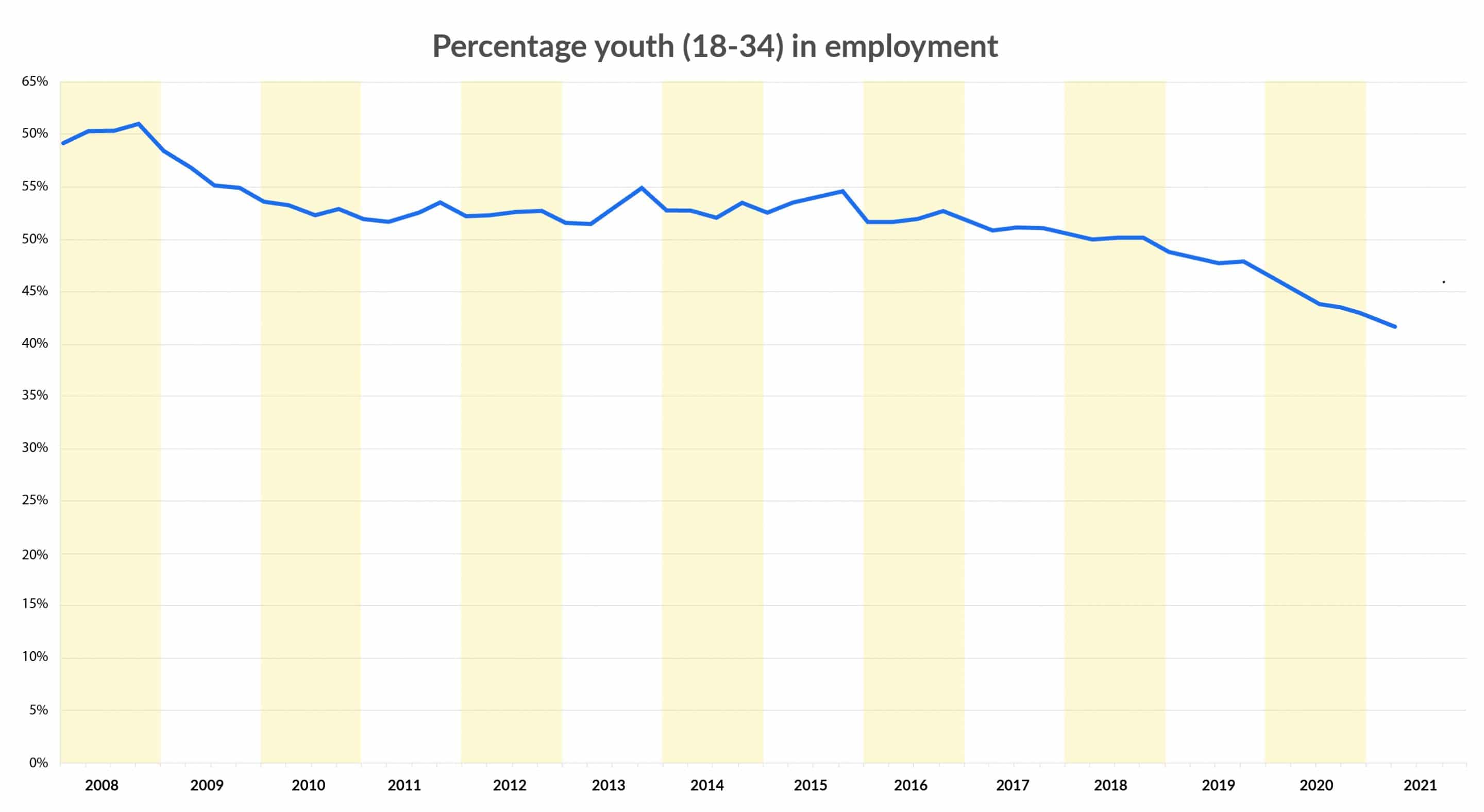

Results from the latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey show that employment for youth aged 18-34 has dropped to its lowest at 42% since the launch of the survey in 2008. However other measures associated with employment such as permanent contracts, longer-term tenure, and occupancy jobs that are of higher complexity are starting to show promise of returning to pre-pandemic levels.

Source: Stats SA Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) youth employment rates, 2008-2021

Women’s employment was more vulnerable to economic shocks in the height of South Africa’s lockdown–comprising two-thirds of job-losses during the peak of South Africa’s lockdown. And while many jobs were recovered, young women sustained nearly 400,000 job losses between 2020 and 2021, pushing them further behind the starting line. Fewer women are now employed than before the pandemic, further widening the gender gap.

Nearly 60% of young women with jobs were employed in community, social and personal services as well as wholesale & retail–working as clerks, service workers or shop salespersons. These industries faced significant churn and at the start of the pandemic–women in community, social and personal services lost 164 000 jobs, only to bounce back a year later to 16 000 jobs below pre-pandemic heights. Wholesale and retail have yet to bounce back; with net losses of 163 000 jobs. This level of variance shows the marked instability that young women face and the need to focus on more jobs that can withstand economic shocks.

As a result of reduced working hours, the gender wage gap widened over the height of South Africa’s lockdown, in some cases up to five-fold the existing wage gap in some of the least paid sectors.

These sectors are slow to recover as they rely on discretionary spending and social mixing. While men, too, work in the informal economy, they are more likely to be in the construction or transport sectors, which by their nature bounce back more quickly to equilibrium. Even in the formal economy, young women were more exposed to the pandemic’s effects, seeing more than double the rate of retrenchments compared to men, in 2020. In this case, young women’s lower representation in formal-skilled and managerial roles, and their lower rates of union protection, likely contributed to their greater exposure. As a result of these structural factors, women accounted for the majority of the unemployed throughout the period, as well as the majority of the net job losses recorded between any two time periods.

However, some jobs did grow in numbers despite the pandemic. Harambee’s own data shows that call center jobs increased, representing 10% of Harambee jobs by Q4 of 2020. We can put young women back on the path to recovery with programmes designed to grow jobs and reduce barriers to entry into these job families,. such as Harambee’s partnership with CallForce and Vumatel in Soweto, creating township-based work-from-home opportunities for women in global business services.

We also know that when sectors intentionally organise themselves for inclusive growth, they can meet the needs of multiple stakeholders—creating jobs and filling them with young people who are well-suited but who have traditionally been locked out. A case in point: the plumbing sector, where Harambee is working with partners in the industry body to open new qualification pathways, raise the profile and effectiveness of apprenticeship and lower barriers to young women who are recruited from within the SAYouth network. The result: more than 50% of the enrollees in these new programmes are women, and employers report that they perform as well as or better than their male peers.

To build resilience in young women’s employment, we need to lower the barriers that keep them out of the most resilient and growing sectors of the economy.

1. Harambee calculations based on data from Quarterly Labour Force survey, Statistics South Africa, microdata distributed by DataFirst (UCT)

2. Ibid

Figure 1: Opportunity for inclusive growth exists in organised economic sectors if we can lower young women’s barriers to entry

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2021

On top of their greater exposure to job loss and lack of protection, young women shouldered the extra burden of unpaid care as schools and daycares were shuttered.

While studies confirm this is a global phenomenon, South Africa experiences a particularly large gender imbalance. The extra burden of childcare and the demands of home-schooling have sapped young women’s time and reduced access to digital devices which are particularly vital to informally-earned household income. Those with younger children are hardest hit, compounding the negative impact on young women. Since women make up the majority of workers in the education and childcare industries, when these facilities close they are doubly hit by the loss of paid care work and the increase in unpaid care work.

The recovery of participation in ECD programmes by April/May 2021 to 36%—close to pre-pandemic levels—helped many women re-enter the labour force, but not enough. A recent study suggests that investing in ECD programmes can generate over 400,000 new jobs in South Africa. When we invest in expanding ECD programmes, young women doubly benefit: new earning opportunities are created and the unpaid care constraints that limit women’s access to these are lessened.

Figure 2: Investment in care givers results in increased women’s participation in the labout market

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2021

Given that young women shouldered the brunt of job losses, you might expect they would be the majority of recipients of government grants for the unemployed during this period.

Young women were underrepresented as recipients of the unemployment insurance fund (UIF), because their employment was more likely to be informal, temporary and insecure—they weren’t even registered in the UIF system. Young women were disproportionately ineligible to access the government social relief distress grant (SRD). Of the estimated 2.7 million individuals who received the SRD grant in June 2020, two-thirds were men, even though two-thirds of those who lost employment between February and April 2020 were women. This was because those currently benefiting from existing grants–like the Child Support Grant–were ineligible for the social relief distress grant. As a result, the majority of unemployed young women with caregiving responsibilities were ineligible for the grant. Fortunately, this inequity has been recognised and along with extending the SRD grant, the government last month announced expanded eligibility criteria to include unemployed caregivers who receive the child support grant.

However, the pandemic has also offered promising evidence that there are other ways to target government spending in support of young women, that increase both their income in the short term, and their employability in the long term. The government’s stimulus spending has had a disproportionately positive impact on young women—at least 59% of recipients in programmes that created jobs were for women, and 97% for youth. Our analysis of the government’s stimulus spend suggests that for every 1 ZAR spent on the stimulus programme, 69 cents were used to benefit young women.

We can build on this in two ways. One, by creating more of these programmes that target spending on young women. And two, by turning them into on-ramps back into the labour market. Here, SAYouth.mobi as a platform can play a vital role pathwaying young women from a “foot in the door” programme towards new skills,opportunities and onward progression.

It is clear that, instead of coming first in a time of crisis, women and children came last thanks to the compound impact of these persistent inequalities. While we have made progress reducing these inequalities in recent years, the long-lasting effects of the pandemic risk reversing it. Yet, it is also clear that we have several levers and tools to mitigate this risk. Now, we need broad consensus and focused, urgent action to use them.

3. Harambee calculations based on data from the Employment Stimulus Dashboards, accessed July 2021

Figure 3: Targeting governement stimulus spend towards women will result in positive labour market outcomes

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2021 / South African Government, 2021 https://www.stateofthenation.gov.za/employment-stimulus-dashboard

Harambee in the News

30 Jan 2026

Harambee in the News: January

A snapshot of where Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator was featured in the media this month, reflecting ongoing conversations around youth employment, inclusive hiring, and the partnerships helping to connect young people to meaningful work opportunities across South Africa.

Harambee in the News

18 Feb 2025

Harambee in the News

15 Jan 2025