SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

South Africa continues to face multiple overlapping challenges: the economic fallout associated with COVID-19, persistent electricity outages, high inflation, food insecurity, high oil prices and growing inequality. Throughout all of these crises, young women continue to be hardest hit—triply exposed by being in jobs that are most exposed to financial shocks, being least covered by social protections such as the Unemployment Insurance Fund, and facing additional burdens of household duties and unpaid care work that exacerbate economic poverty with time-poverty. These factors compound, severely impacting their ability to look for work.

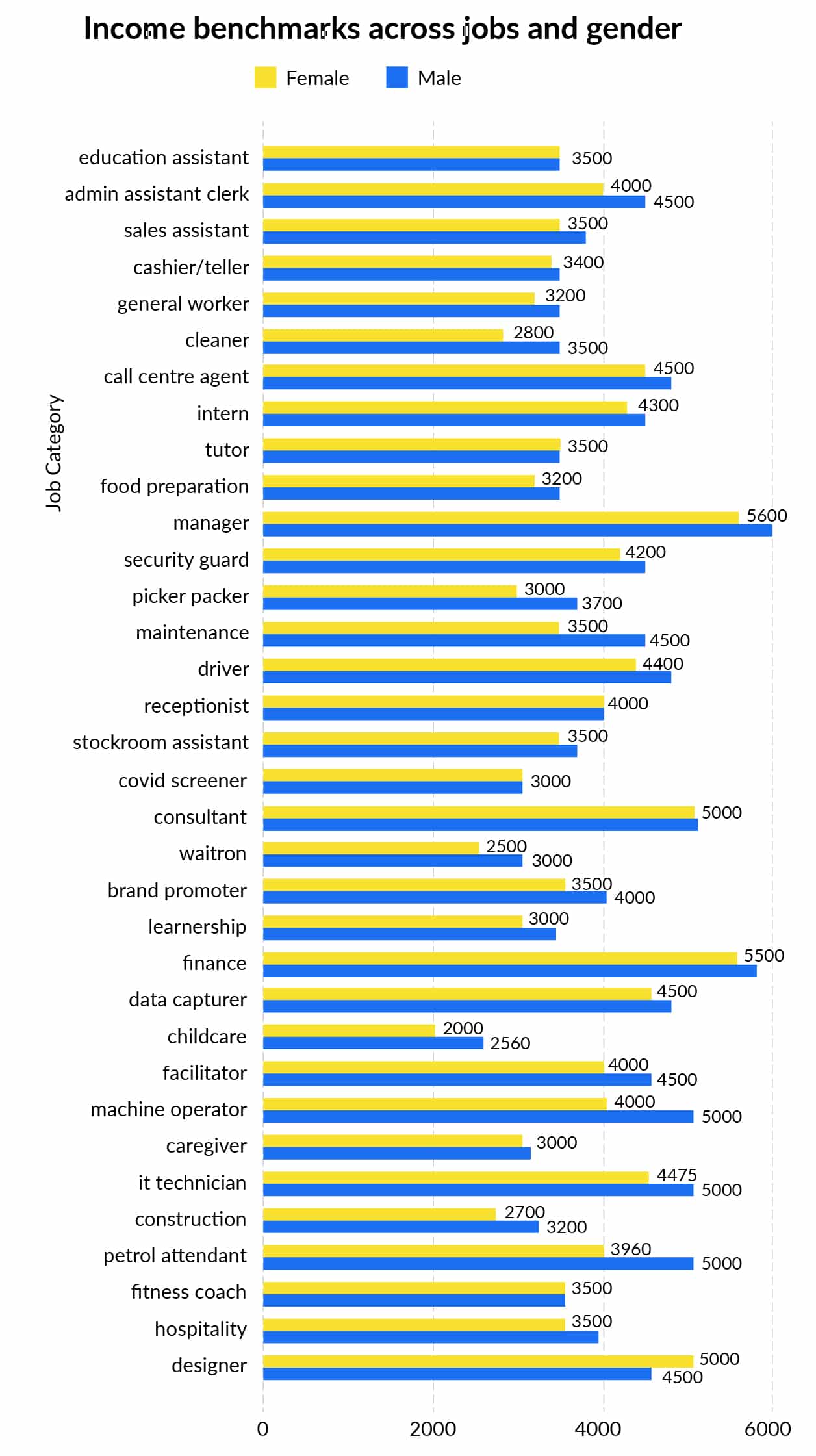

Harambee’s analysis of the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) and the SA Youth network suggests that, on average, women possess more educational qualifications but remain less employed and economically active. This proves Harambee’s decade-long hypothesis that more schooling and qualifications alone will not translate into economic opportunity, particularly for those most excluded from the labour market. Our detailed analysis of income by job types suggests that linking young women to opportunities, even at scale, will not help level the playing field. Advocacy for gender equity—by breaking barriers to inclusion and advocating for equal pay for equal work—is critical.

Harambee’s analysis over this past year reveals that women earn less than men across almost every occupation type and job family. This study of youth income and earnings is, in fact, a study of gender disparity.

So, this August, while we celebrate Women’s Month, Harambee continues to shine a spotlight on the gendered dimension of youth employment in South Africa and the specific actions we can take to address this.

Formal sector jobs pay well and are relatively stable. But barriers to enter remain significant, and women earn less across nearly every job type. Designing for gender inclusion and pay equity can shift this landscape.

Harambee’s analysis of formal sector jobs suggests that the median income within reported formal sector jobs is both relatively stable and relatively high, around R3,500 per month, with a range of between R2,200-R5,000 per month, with higher paying jobs in growing sectors such as Global Business Services and Finance.

A gendered analysis of earnings across all occupation types—from sales assistants to software testers—suggests that in the formal sector, men earn more than women. On average, young men earn at least +6% more than men on median earnings, and +12% more than women if we consider the mean, with the gap widening over time.

What actions can be taken to address this? Firstly, breaking barriers to women’s access to higher-paying and high-growth entry-level jobs is critical. SA Youth itself disproportionately places more women than men into earning opportunities (a rate of 68% compared to network membership of 63%). We need more partnerships like the one with IOPSA, NBI and BluLever to pathway young women into high-growth sectors like plumbing apprenticeships–a multi-stakeholder partnership with IOPSA on the ARPL programme comprises a cohort of 13% women, against an industry that is less than 3% female; for new entrants into the sector, through a partnership with NBI and BluLever, our cohort is 54% female–creating new pathways in traditionally male-dominated industries.

We also need a targeted focus on the inclusion of women in incentive schemes to promote job creation in high-growth, new sectors, extending this successful approach within and beyond the Global Business Services market, where of 3,731 new jobs created in the sector in the past quarter, 65% were for young women.

But pay advocacy for pay equity is critical—here, government regulations and employer advocacy can encourage pay parity instead of reliance on market mechanisms alone, else as the data suggests, we run the risk of perpetuating gender inequity.

Figure 1: Women’s media earnings is less than men’s for most job categories

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator

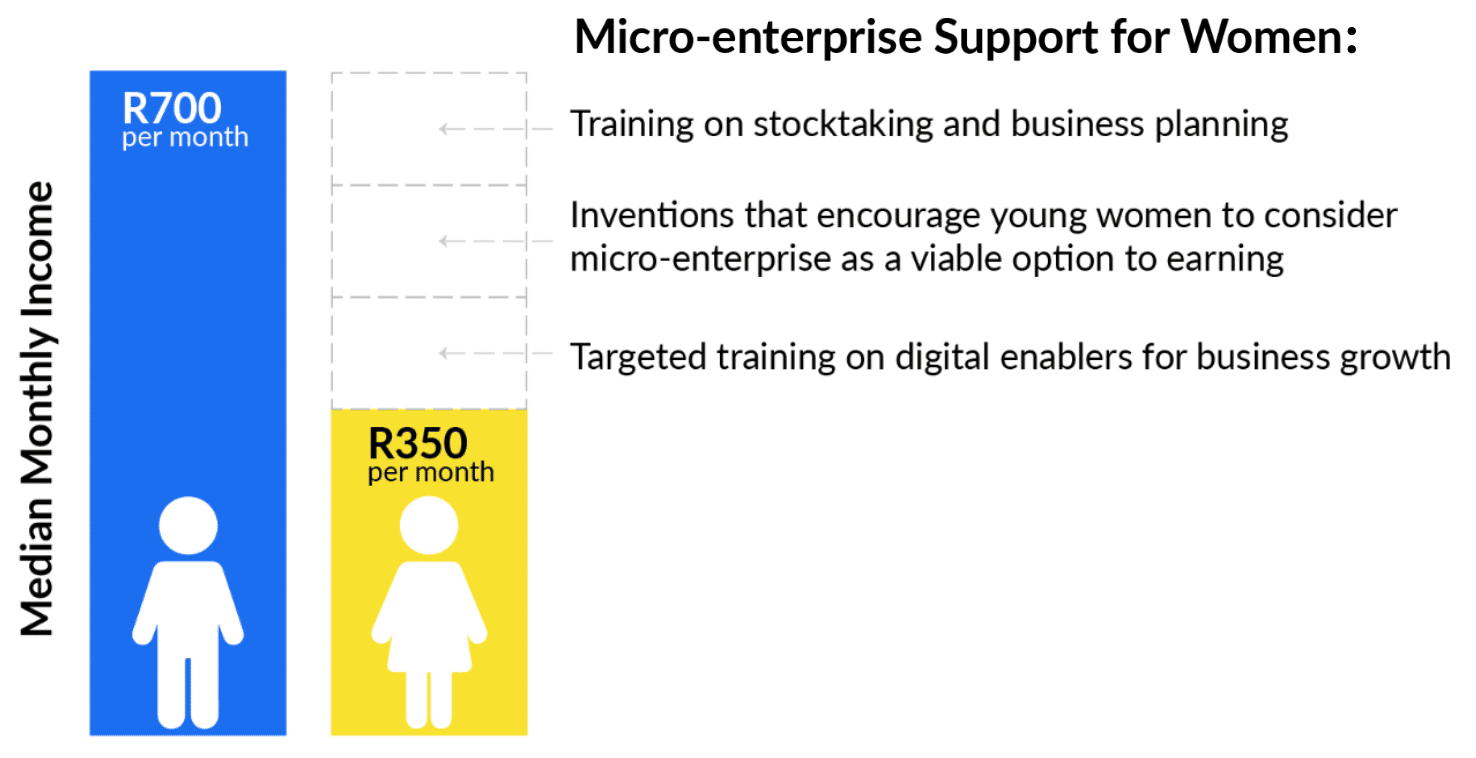

The hustle economy is precarious, and even here, men earn up to 50% more than women. Women have less time to hustle and may be constrained by social norms into selling goods over services. Targeted support for micro-enterprise for women can have a significant impact.

Harambee’s analysis of micro enterprise reveals that while young people hustle to survive, this income is precarious and inconsistent, and on average much less than all other forms of income. Median income for hustling is around R700 per month—with women earning almost 50% less than men.

While the data is hard to interpret given inconsistencies of reporting income within the informal economy, earnings differentials between men and women may be a result of different kinds of entrepreneurial activity. But, earnings may differ also because women have less time to hustle, given additional household responsibilities and other social constraints. Also, selling “goods” (such as selling snacks like chips and vetkoeks) tends to be associated with higher incomes, while selling services (such as providing security services, delivery, washing and cleaning etc.) is associated with lower income. On average, women sell more goods than services, and selling goods results in “lumpy” and inconsistent income—because purchases of stock are driven by sales, and sales and purchases tend to happen irregularly.

Training on stock-taking and business planning could help young women like Nonhlanhla Cele earn a more sustainable income going forward. Nonhlanhla joined the SAYouth network and then was able to start her own small business selling airtime, electricity, chips, sweets and cakes. With some support, she has been able to add a 10% profit margin to everything she sells and bring an extra R50 a month into the household. But during the Durban riots of July 2021, her business came to a standstill. As things started to open up again, Nonhlanhla’s ability to meet restored demand was limited by her reduced existing stock. Nonhlanhla realised that she needed to diversify her offering and get a stable space to trade and store stock, in order to ensure continuity for her income. There are many women like Nonhlanhla who can benefit from targeted micro-enterprise support to build business, versus personal, resilience.

Figure 2: Young female entrepreneurs earn almost 50% less than their male counterparts

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator

Further, when Harambee investigated young people’s “entrepreneurship orientation,” as measured by an index of motivation, accomplishment and long-term planning, women on the surface appear to be less business oriented than men. This may be due also to the fact that women also have less time to look for work, amplified by the fact that they have additional burdens due to household work and care obligations. However, while those with higher levels of business orientation typically had bigger businesses and more revenue, those levels had an almost negligible impact on profit margins. Thus, while business orientation may be important, the entrepreneurial activities of young on average, do not optimize incomes. We need targeted interventions to enable young people overall, and women in particular, consider micro-enterprise, but to be equipped with the skills to run a broader range of businesses and see this as a viable pathway towards economic opportunity.

An example of this is Harambee’s partnership with Qwili, a tech start-up that provides a digital platform for aspiring entrepreneurs to buy inventory at wholesale prices, which they can then on sell to earn a commission. Harambee and Qwili currently identified 31 young people from our network to provide training in entrepreneurial skills, including training on the on-selling opportunity and R500 in start-up capital to support sales and ongoing hustles. 85% of the participants are women, and early evaluation suggests that with targeted training on how to use digital on-selling platforms, young women can earn consistent and sustainable amounts from micro-enterprise.

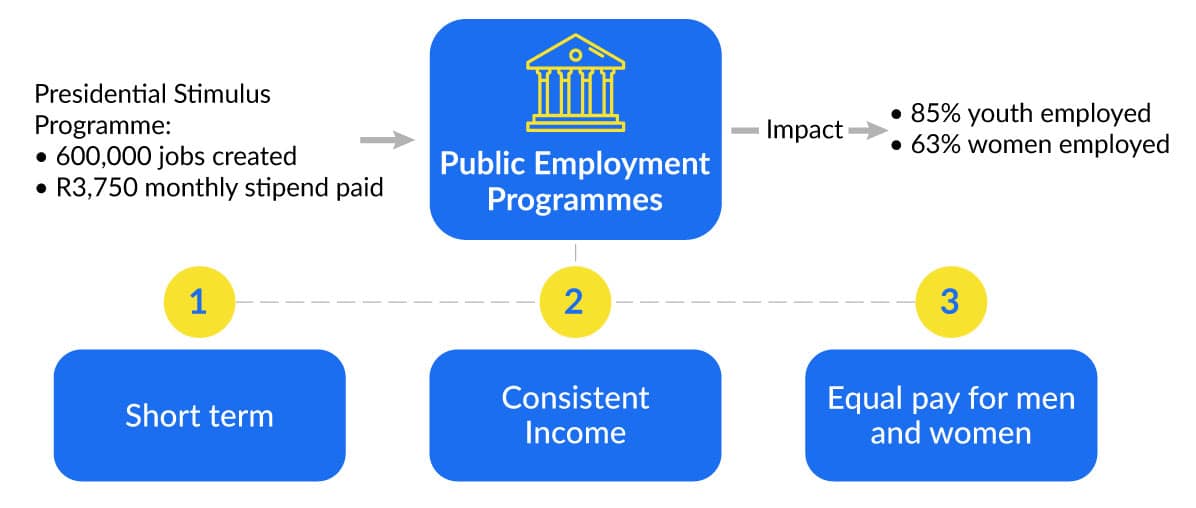

Public employment programmes—while short term—provide a stable income and have gender equity baked into their very design.

As our previous analyses has suggested, there is little doubt that public employment programmes—particularly in times of economic crisis and recovery—can serve as an economic lifeline for our most excluded young women and men.

Harambee’s analysis of incomes within public employment programmes—comprising over 60% of SA Youth’s 860 000 pathways—suggests that this short-term income is consistent and equitable by design, as these programmes are paid equally per definition. Incomes within public employment programmes vary with days worked per month, with a mean of R2,650 and a median of R1,550 per month. The Presidential Stimulus Programme created over 600,000 better-paying opportunities, with an average stipend of R3,750, disproportionately impacting young people (85%) and women (63%).

Public employment programmes specifically help young women like Noxolo Gumede. Growing up in Newcastle, Noxolo was always passionate about fixing things and after matric, was funded by NSFAS to study as a boilermaker. However, she found it hard to get an apprenticeship to allow her to do her trade test and complete her diploma, leaving her severely discouraged. After hearing about SA Youth on Facebook, she registered, applied for and landed an Educational Assistant position at a school in her area. This opportunity has enabled Noxolo to gain financial independence and invaluable work experience, and, she says, given her hope.

Increasing opportunities within the care and social economy—which includes education—can have a triple impact on our economy and society. It can impact the recipients of care while freeing up caregivers’ time to look for and engage in other work and create job opportunities within the sector. A recent analysis of South Africa’s ECD sector alone suggests that increasing childcare coverage could lead to an 8-percentage point increase in the labour force participation rate, or roughly 3.1 million people. Furthermore, for every R15 invested in childcare programming in South Africa, primary caregivers could generate up to R105 in benefits through entering the labour force. This multiplier effect will not only impact individual lives but will also trickle down to the community economy level. Ironically, even childcare jobs appear to have a gender pay differential. Evidence from Harambee’s data of young people in our own network indicates gender wage disparity, where men may earn up to 50% more in paid childcare jobs compared to female contemporaries in the same role, suggesting that pay equity and advocacy across the board is critical.

Despite the trends, it is heartening to note that women continue to signal their willingness to work by joining platforms like SA Youth and applying to Public Employment Programmes in much greater numbers than men. As noted, 65% of the SA Youth network is female, despite our gender-neutral positioning. The success of programmes like the Employment Stimulus /BEEI, as well as sector-specific initiatives to break barriers and advocate for gender equity, suggest that norms and systems stacked against young women’s employment can be ‘rewired’. Precarity and exclusion are not inevitable, and we owe it to young women like Noxolo and Nonhlanhla to design them out.

Figure 3: The characterisitcs and impact of Public Employment Programmes

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator

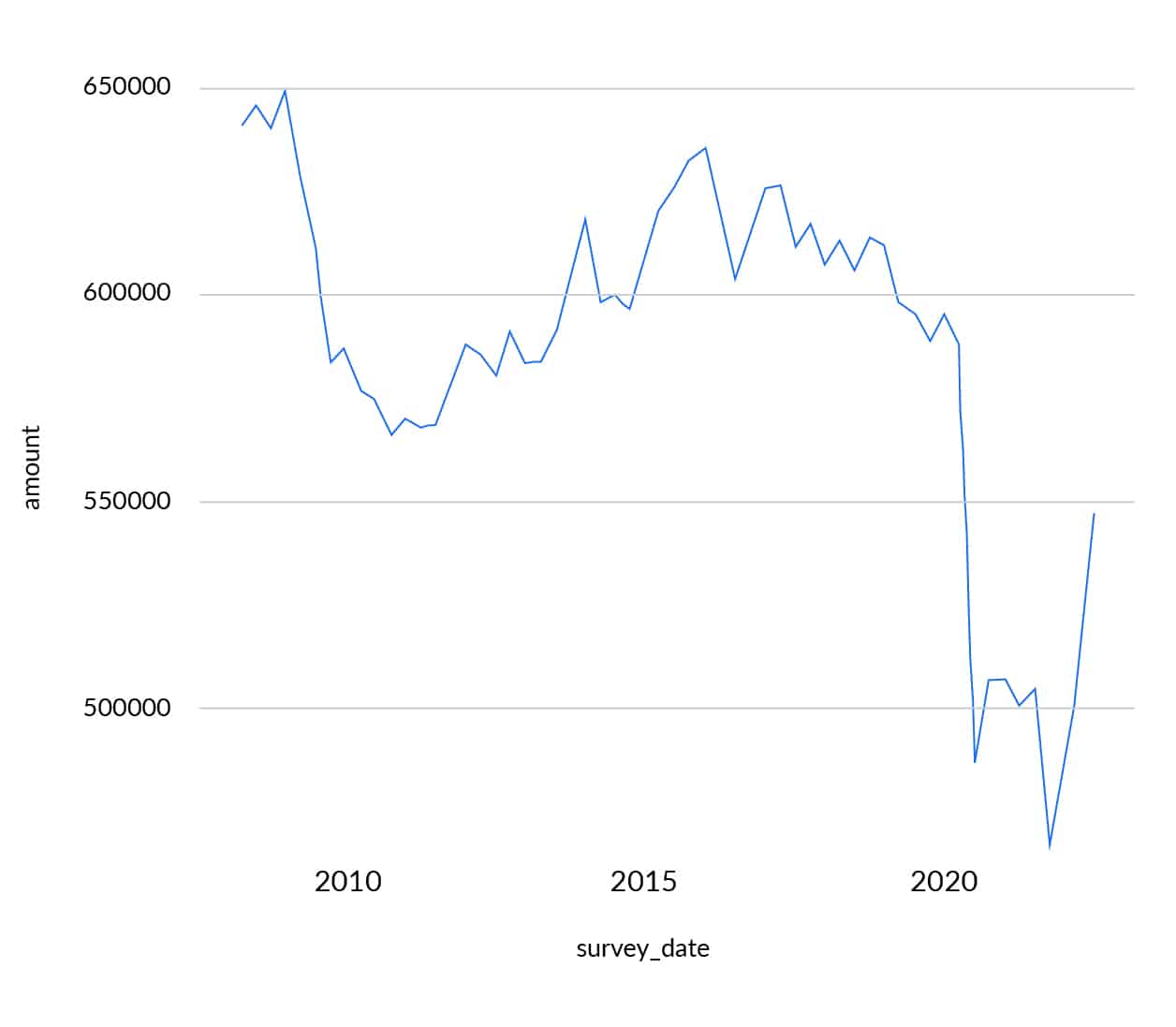

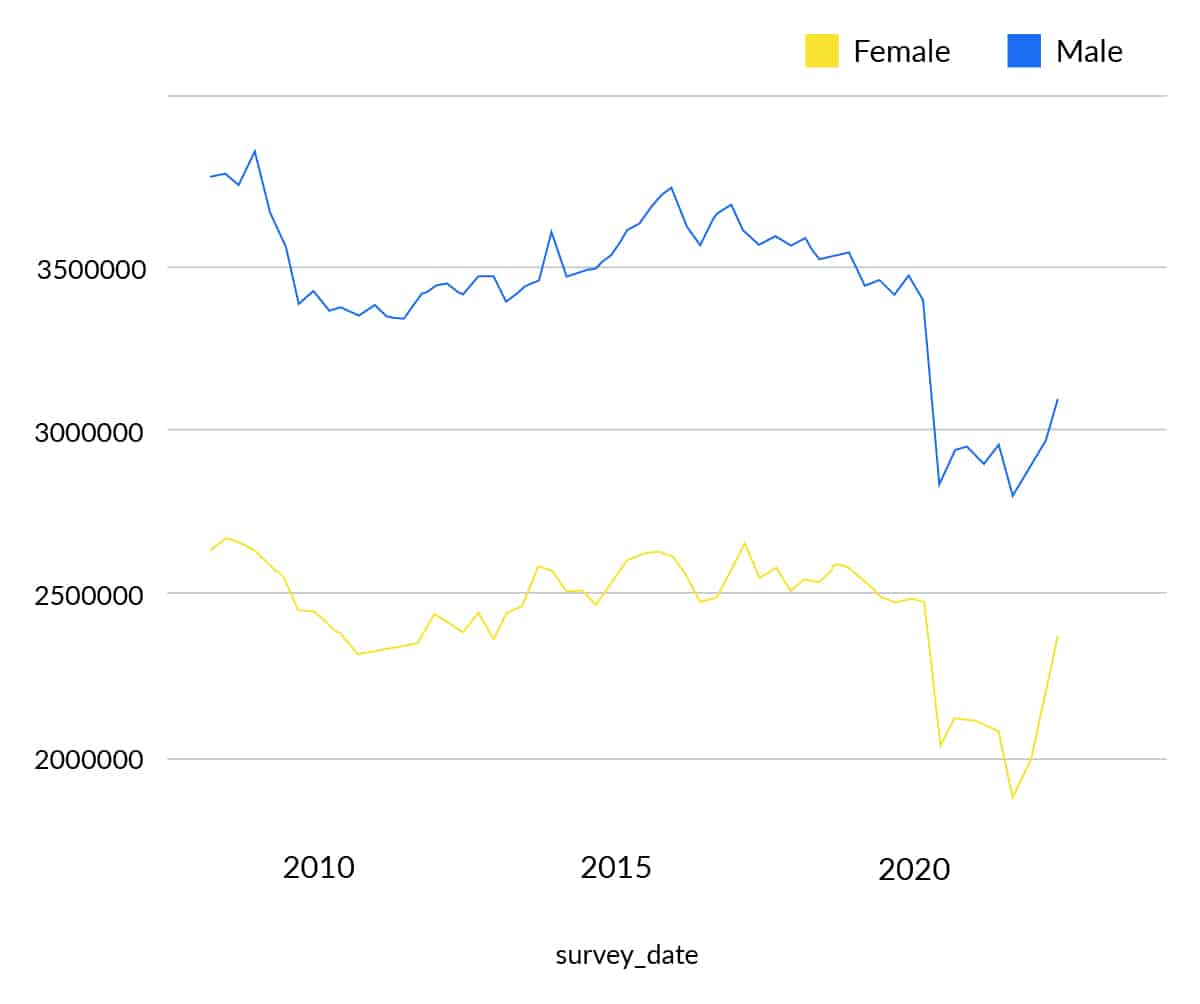

Youth employment data drawn from the 2022 Quarterly Labour Force Survey Quarter 2 shows that the number of young people continue to rise. Although not back to pre-pandemic levels, ± 430,000 youth jobs were added year on year.

Figure 4: 430,000 youth jobs were added year-on-year

Source: Stats SA QLFS 2022 Quarter 2 Data

Figure 5: Females have been ‘rebounding’ better

Source: Stats SA QLFS 2022 Quarter 2 Data