SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

In January 2024, South Africa achieved the highest ever matric pass rate of 82.9% and in April, we will commemorate 30 years of democracy. Both of these milestones are momentous and worthy of celebration but they are also weighed down by some staggering facts: nearly nine million youth are not in education, employment and training (NEETs) and of these NEETs, 53% have not finished matric and have dropped out of the education system entirely. This is potentially a lost generation if we do not actively try and reintegrate it into the economy.

South Africa’s economy, forecasted to grow at 1% in 2024, is still under construction and is still struggling from a series of crises: the 2008 recession, the COVID-19 pandemic, and a legacy of spatial exclusion. This economy-under-construction disproportionately impacts our most vulnerable: youth, women, and persons with disabilities and (re)building it requires a variety of solutions. One of the most important of these is stimulating job creation and we need to continue deploying a variety of strategies to create pathways to work: strategies Harambee has iterated and seen the promise of over the past 12 years, resulting in 1.2 million work opportunities recorded.

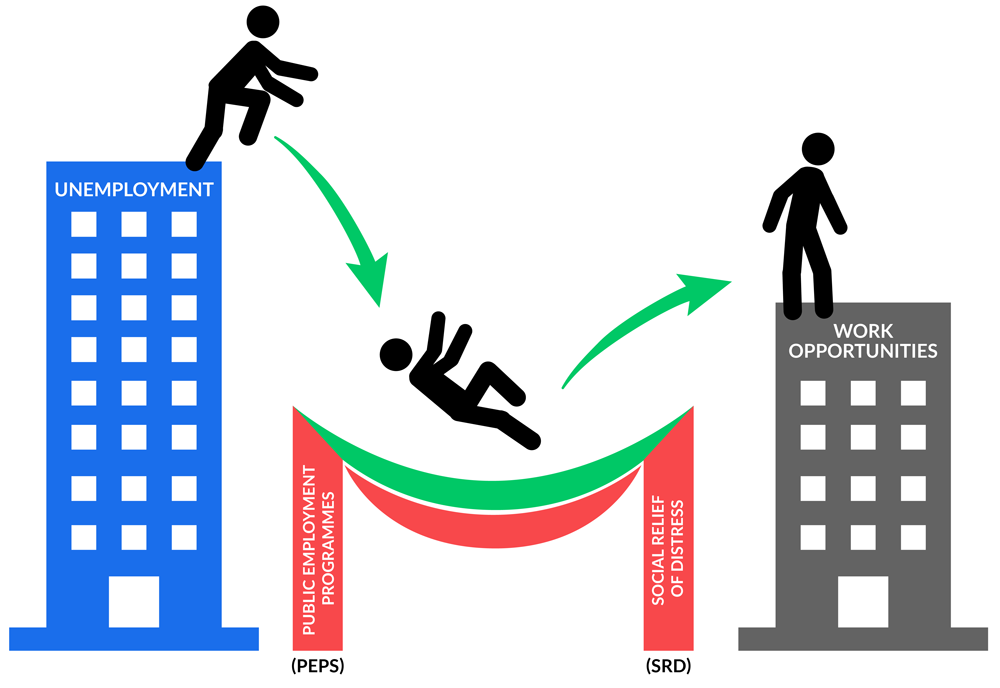

New and wider gates into the jobs of today are also required: ones that assess for potential, not past performance alone. Furthermore, we need safety nets in the form of support mechanisms such as social welfare grants and temporary work opportunities. These are often perceived as safety nets alone, which keep young people from falling out of the economy but, if well deployed, can turn into trampolines which young people can use to spring into other work. Finally, we need to actively build foundations for new jobs and scaffold youth into new opportunities that emerge in the formal and informal sector.

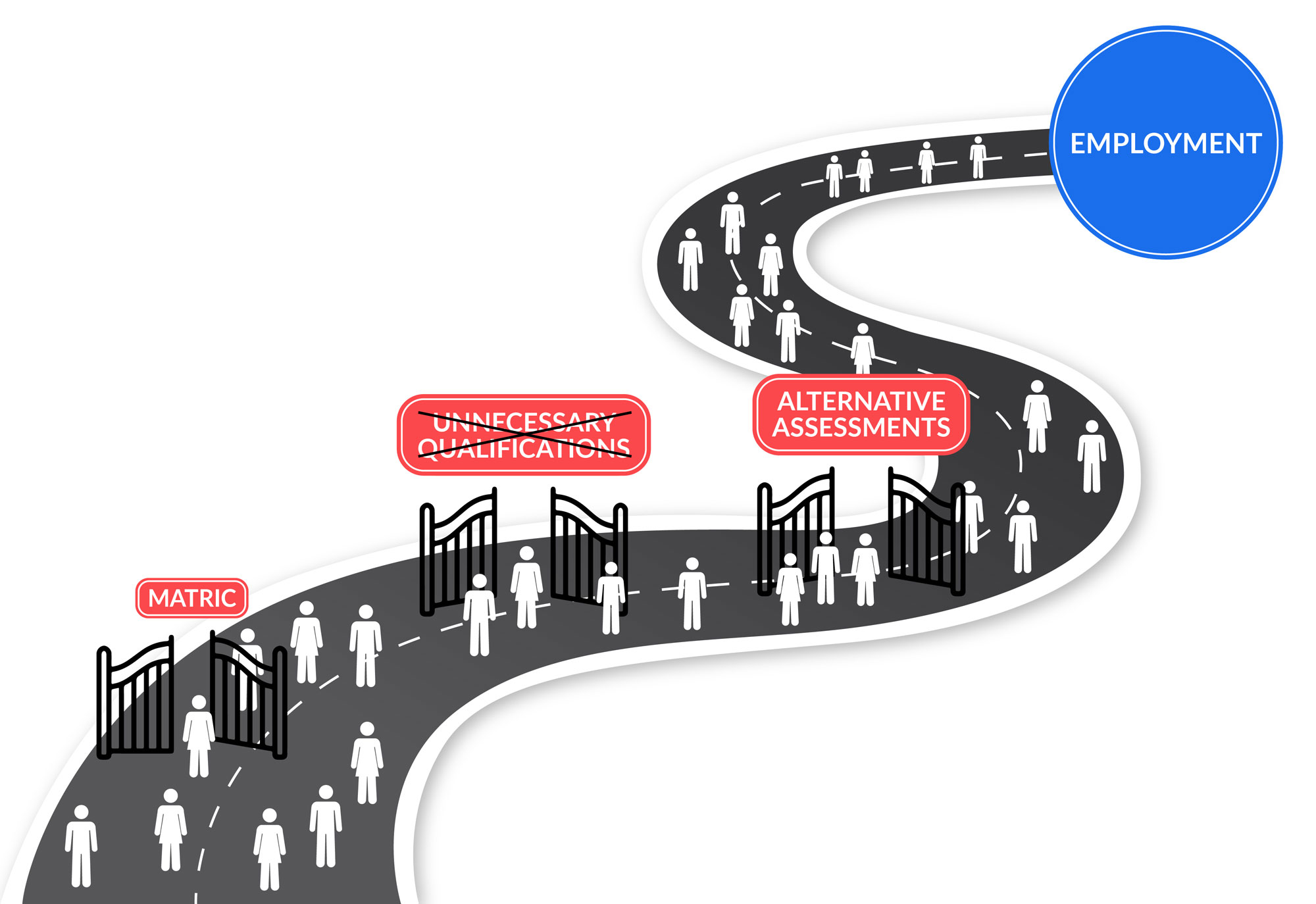

There are many ‘gates’ that keep youth out of jobs. We need to widen these gates, without lowering the bar.

Apart from the record matric pass rate of 2024, another record was the 40.9% bachelors pass rate, representing 283 000 youth who can now apply to enter university. These are some of the lucky few who make it through the ‘gates’ and whose chances of getting employment are significantly improved.

But while matric matters, it can also act as an unfairly narrow ‘gate’ into the labour market, and one that also keeps talent–particularly young women and people with disabilities–out of the labour market. A person with a degree is twice as likely to be employed than a person without a matric and even matriculants have an expanded unemployment rate of 51%. When employers rely purely on these proxies, Harambee’s experience suggests, they might miss out on thousands of candidates who are better suited to the role but do not have the qualifications – matric or otherwise – to even get noticed.

Our experience suggests that many entry-level jobs can be performed easily by those with a matric, and in some cases even less than this. While matric is indeed a useful gate for university access, the labour market may be different. We need employers to widen these ‘gates’ to entry level jobs and to help them do this, we need better signals of competency, better matches, and we need to actively advocate for them to hire these youth, by showing evidence of returns.

Firstly, we need assessments for entry-level work that are independent of school results. These are focused on the actual abilities needed to perform work. Counting money, for example, does not need an employee to be able to solve algebraic equations. Harambee has over a decade of experience in administering alternative assessments and tools that focus on problem-solving and logic, such as the fluid intelligence test called the Concept Formation Test which formed part of the TRAM Psychometric Battery. Fluid intelligence refers to the ability to reason, think flexibly and solve abstract problems. This ability is considered independent of learning, experience, and education. But these were expensive, requiring face-to-face and lengthy assessments to demonstrate potential. Recently, however, our platform innovations have been able to scale our approach. Partnering with assessment experts, Harambee developed shorter, mobile-friendly tests to identify work seekers with potential for higher complexity work.

This mobile problem solving assessment on SAYouth.mobi, revealed that 20% of those performing poorly in matric maths show good enough raw problem solving potential to be considered for entry level admin roles. This suggests that 20% more young people who may have not made it through other ‘gates’, can be considered for roles reserved for those with higher marks: an example of widening the gate without lowering the bar. This is also significant for another reason: it shows how technology can help scale our inclusive assessments. We have already conducted 170,000 such tests in just a few months, averaging around 1,500 per day which in the past would have taken two years, four full time staff in in-person facilities, and R500,000 in transport stipends to do a similar number of the previous generation of assessments. We will need more employers to partner with us to trial these new ways of assessing potential–and to build inclusive onboarding programmes to support this potential.

Many jobs can be done well with just a matric and an example of these are found in the Global Business Service (mostly call center) industry, which has grown and benefited from hiring less experienced youth and has seen high returns on investment. These include cost savings due to reduced attrition and absenteeism and higher performance (Everest Group, Impact Sourcing report). On SA Youth, we try to offer more listings that do not require a matric. In a sample scan of private sector job postings online, fewer than 3% of job listings (predominantly in direct sales and retail) are explicitly open to those without a matric. The SA Youth platform has disproportionately more – at least 10% of private sector listings do not require matric – and if we add public employment programmes, the percentage of jobs not needing matric on SAYouth would increase to 40% (half of the positions in the DBE school assistant program did not require a matric).

By dropping unnecessary qualifications and focusing instead on job-specific requirements and alternative assessments, we can widen the ‘gates’ that currently restrict access to the labour market. As a consequence, we can increase the ready talent pool available to employers that are a better match.

Figure 1: New and wider gates into the jobs of today

All forms of ‘safety nets’ are needed and, if well deployed, these can serve as trampolines to other work.

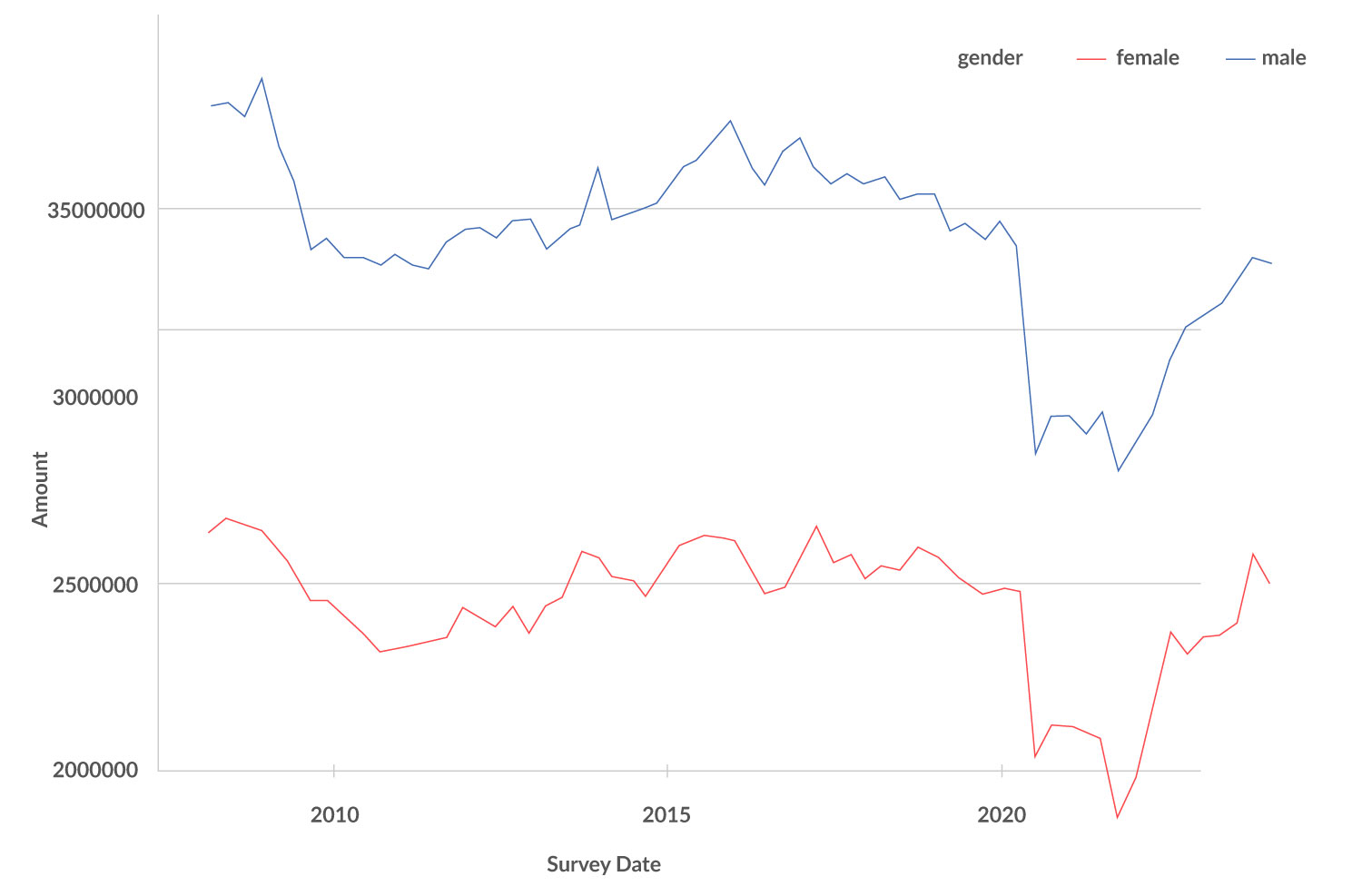

Despite recent and significant upticks, our long-term analysis of QLFS data suggests that the economy has been shedding jobs for youth since the 2008 economic crisis, moving from 6,4 million employed youth to 5,9 million employed youth. We are barely back to COVID-19 levels of youth employment which were not great to begin with. In the absence of overall macroeconomic growth, ‘safety nets’ and initiatives like Public Employment Programmes (PEPs) are not just an option, they are a necessity.

But ‘safety nets’ often come under fire for being only that: ‘safety nets’ that do not stimulate economic growth. This is a false notion as these ‘safety nets’, when well deployed, can actually act as trampolines to opportunity as the economy recovers. South Africa deployed many ‘safety nets’ and welfare programmes that prevented millions–particularly its youth, and women–from plunging into poverty over the past two years. We outline the impact of two in particular.

The Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant of R350 per month to those without income has led to major reductions in food poverty (Orkin et al, 2022). Studies show that the impact of the SRD has reduced the number of people living below the food poverty line by roughly two million people. There is increasing evidence that these grants also have notable, albeit small, labour market effects. These studies suggested that receiving the grant increased the probability of employment by three percentage points, and that these employment effects were driven by effects on wage employment in the formal sector. The study also showed a small effect (+1.2 percentage point) on the probability of trying to start a business. Harambee and our research partners continue to examine the job search activity and outcomes of grant recipients to be able to add to the evidence base that these safety nets can have positive labour market outcomes.

In 2020, the South African government’s launch of PEPs was a direct response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Presidential Employment Stimulus has directly created 1.8 million jobs and livelihood opportunities, of which the Department of Basic Education’s Basic Employment Education Initiative (BEEI) has been well documented for being inclusive. The initiative employed about 245,000 young people per phase to assist schools across the country, and it has recently been extended. With over one million placements of young people at 23,000 schools, the BEEI is the largest youth employment programme in South Africa’s history.

But these programmes go well beyond the function of providing ‘safety nets’ to youth without any options. These “circuit-breaker” programmes have had ripple effects beyond the placements themselves. The skills gained from these programmes such as administrative skills, communications, and teaching skills have proven themselves transferable and have given youth a step up into other PEPs and job opportunities. Many of these opportunities have created pathways into other related opportunities such as tutoring, administrative assistants and IT technicians. On SA Youth alone, those who had undertaken the DBE Phase 1 programme were on average 7% more likely to access jobs in admin and education related fields, compared to those who applied but did not get the job in Phase 1. This might be because they were able to bank some of the admin skills they learnt during the programme. We are still evaluating the impact of these programmes on labour market transitions overall and do not yet have evidence of systemic shifts in labour market outcomes but this early data suggests an interesting shift in the type of jobs that participants access after the programme.

Furthermore, these programmes keep our youth engaged and productive. BEEI positions drove up traffic on SA Youth 30x, from an average of 2,000 visits per day. Why is this important? There is initial evidence that greater engagement on platforms correlates to higher employment outcomes: youth who spend three days on the SA Youth platform in any given period have a 10% higher chance of employment over those spending one day on it.

Early evidence suggests that well-run PEPs can stimulate the economy, and springboard youth into other work opportunities, suggesting that safety nets can, in fact, become trampolines, in the right circumstances. Research by the Learning Trust evidenced that the Social Employment Fund programme enabled over 6,000 work opportunities, and in addition to increasing household incomes, improved work readiness, increased access to other concurrent opportunities such as micro-enterprise, and increased access to opportunities within the host organisations of the programme.

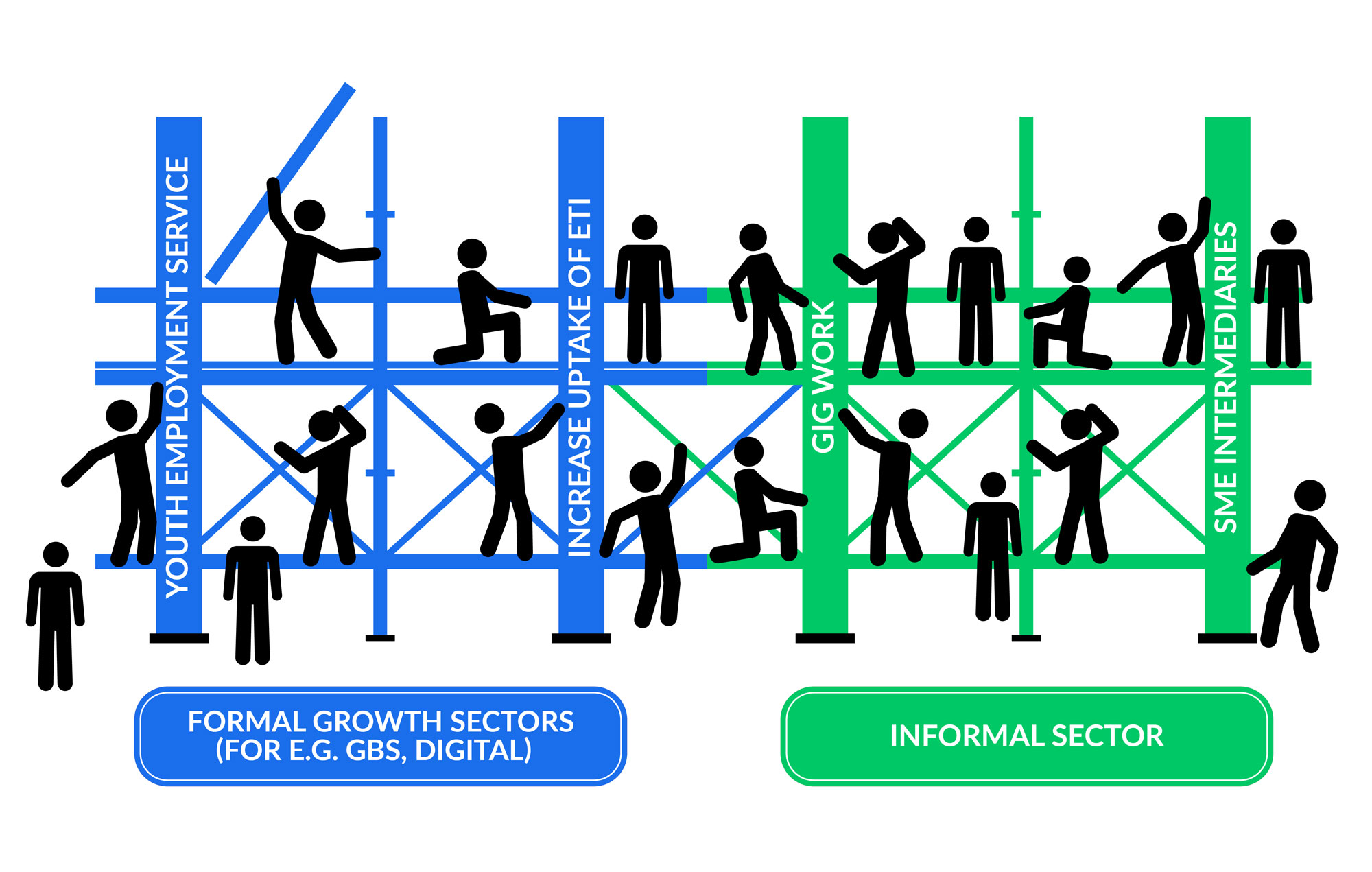

We need ‘scaffolding’ for all forms of work, and collective efforts to rebuild the economy.

South Africa’s economy has inched towards a single digit growth rate from below 1%. Many business leaders, in partnership with government, have zeroed in on key policy priorities such as logistics, energy transformation, and crime and corruption to try to shift this number. Re-centering youth employment in these priorities remains critical. Harambee’s analysis of the GDP growth rate since 2008 suggests that, while job creation does broadly track GDP growth, since 2015, youth jobs have decreased despite gains in GDP. For a country with such a large youth population, the promise of GDP growth alone will not address the massive crisis of an unproductive, disengaged youth cohort.

Hence we need all hands on deck. This includes the safety nets and springboards of grants and employment programs, but also the formal and informal economies creating earning opportunities for youth.

We need to turn to sectors that have a fast job growth rate such as GBS and the digital sector, and encourage these sectors to hire more youth. We also need ‘scaffolding’ in these sectors – youth-specific structures and support – to drive up the hiring of youth. We need to continue to support initiatives like the Youth Employment Service (YES), and increased take-up of the Employment Tax Incentive (ETI), both of which provide scaffolded entry into formal economy jobs. It is important for us to evaluate the impact of these programmes while simultaneously tweaking their effectiveness towards greater impact.

Furthermore, the informal economy remains a risky bet for youth, but it is also an earning space that is growing faster than GDP. According to QLFS data, South Africa’s informal sector contributes 20% of the economy’s earning opportunities for youth, but with a growth rate of 31% over the last 10 years in terms of jobs provided. This is a growth rate almost 4x higher than the formal sector. Given that more youth are entering the informal economy, we need to find ways to de-risk this process and create scaffolding for both youth and SMMEs in this space.

Support through SMME intermediary partners de-risk labour market entry and remove some of the barriers experienced so that young people are able to earn consistently and earn above minimum wage. The combined impact of Harambee’s approach to partnering with intermediaries who support young people to make their own money has resulted in average net incomes ranging up to R4,500 across all programmes, and 69% of beneficiaries being young women. The nature of this support may vary but can include the provision of strategic business support, access to finance, and contracted base earnings.

An estimated 3.9 million South Africans, most of whom are under 30, are already involved in the gig economy which has a growth rate of 10% per year (South Africa Jobtech Landscape, 2023). Scaffolding entry into gig work is another option for young people wanting to enter the labour market. For example, ride-hailing platforms such as Uber and Bolt in particular are expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 17.45%. Commission-based sales opportunities also provide a range of access points to work and earning. Both of these require careful consideration because youth can also fall victim to scams and low-margin opportunities. While SA Youth has seen an increase in these types of listings (from a few percentage points to 10% of reported opportunities) we are actively working with our platform and marketing partners to provide more scaffolding for these opportunities and ensure fairness and resilient income. By obtaining and sharing more information on the opportunity such as its earnings, payment structure, contracting, resources provided and training offered, young people can become informed and more discerning in the opportunities they take up.

To support the construction of an inclusive economy that has a healthy growth rate, we need to deploy a variety of solutions to the crises that have crippled it. Tackling youth unemployment using the strategies detailed above needs to be at the top of this list. We need to widen the gates to the labour market and rethink uneccesary requirements for entry-level jobs by creating better signals of competency and better matches between youth and employers. In parallel, we need to support the effective deployment of ‘safety nets’ – social welfare grants and PEPs that keep young people from dropping out of the economy entirely – while always staying alert to ways we can better show evidence of their ability to ‘trampoline’ youth into other opportunities. While we support employers to widen the gates to jobs for youth, and ensure resilient ‘safety nets’ remain intact, we need to focus on the fastest growing sectors that can offer the easiest and quickest in-roads to the labour market for as many youth as possible. Doing this requires ‘scaffolding’ to increase access to a range of opportunities. A genuine celebration of figures like the matric pass rate and the age of our democracy is possible – and should be anticipated – but only when we can show that those 8.6 million NEETS are confidently taking their place in the labour market, instead of becoming a lost generation.

The latest QLFS figures for October to December 2023 report that overall employment stayed about constant at 16.7 million–with winners and losers.

Quarter-on-quarter, there was a small decrease of 22,000 jobs overall. Notably, youth jobs decreased by almost 100 000, implying that the older workforce had a net increase. The same is true for women, with 80 000 women losing jobs and 60 000 men gaining jobs. These fluctuating trends are a reflection of the volatile earning environment for youth and young women in particular: less job security, higher churn in jobs and shorter durations.

Despite this quarterly result, the annual trends confirm a recovery post-COVID, with 300 000 youth jobs added over 2023. NEETs are also reducing overall, despite quarterly fluctuations. However, we are still not yet back at pre-Covid employment levels for youth.

Overall the QLFS still paints the picture of a stagnant economy under construction. We are still in need of scaffolding and safety nets for those most vulnerable: youth and women.

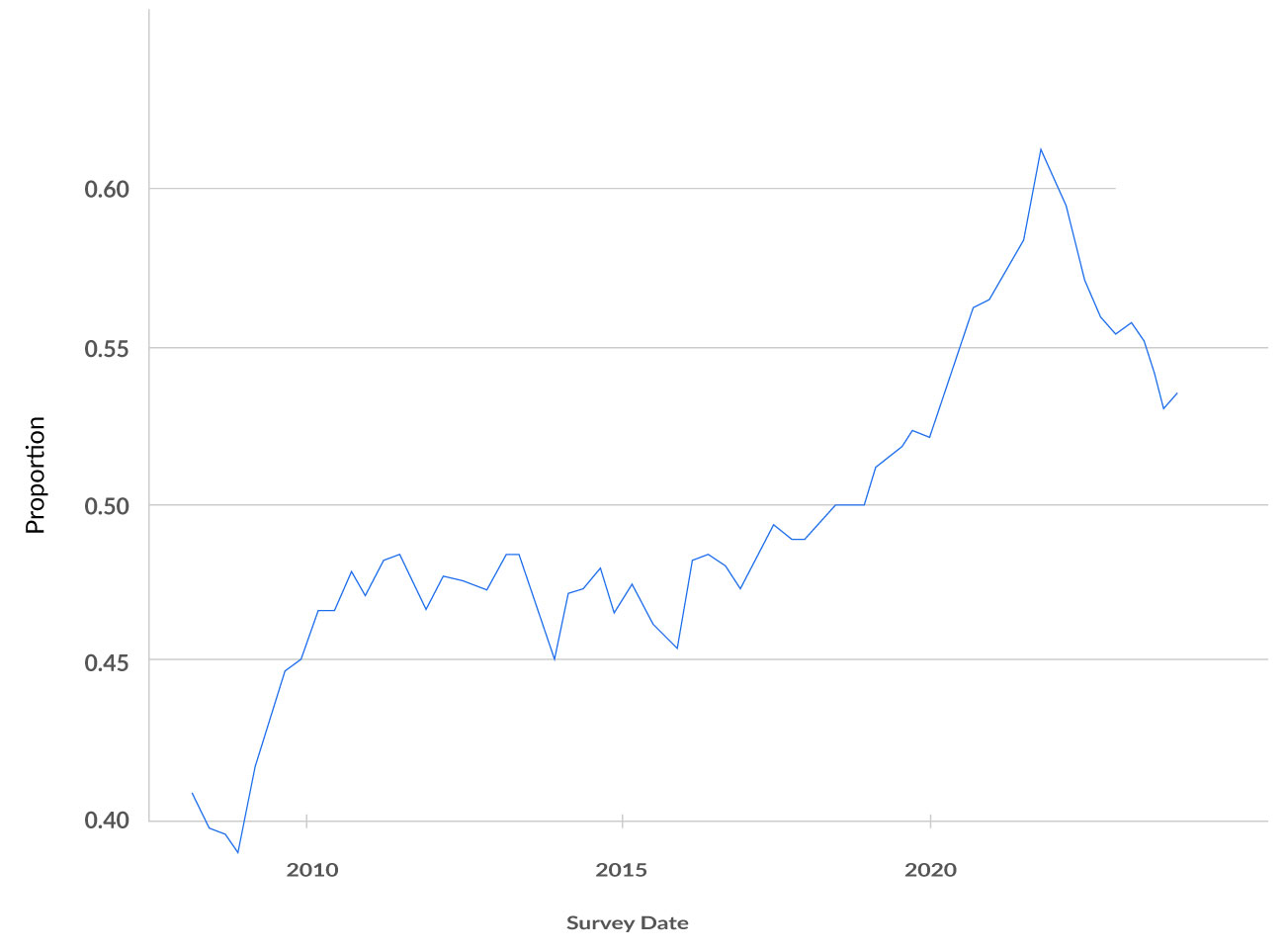

Expanded Youth Unemployment rate:

Youth Employment by gender: