SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

19 February 2025

The start of 2025 fixed all eyes on the matric results and the all-time high pass rate of 87.3%. The release of these results is an auspicious event, painting a partial picture of how young people, and the education system, are faring. But getting a matric certificate will remain more of a mere milestone than a stepping-stone for millions of young people for as long as South Africa’s labour market remains unable to absorb them. This represents millions of youth whose potential remains squandered. And as South Africa aspires to higher economic growth rates—Harambee’s decades of evidence and impact suggests that youth, if included, can in turn drive the economy forward—representing a virtual cycle for growth and shared prosperity.

Each year, approximately 1 million people enter the labour market, exiting the education system at various points, including leaving school before or after matric. Once there, they move in and out of employment. While 400,000 are expected to eventually find relatively stable employment, and another 300,000 will work infrequently, the rest are likely to never work because of low education levels and poor skills. Harambee’s analysis shows that higher education does lead to income opportunities and higher earnings, but young people still end up moving in and out of work to try and earn decent incomes. This churn impacts young people, but is itself a hidden cost to our economy, by limiting the potential, contribution, and productivity of a generation of young people.

Our previous reports highlighted that over the past 16 years, GDP growth has proven a necessary but insufficient condition to address youth unemployment, but it is certainly not the silver bullet to fixing this crisis. Our experience suggests that we need to collectively invest in the five levers we know to have worked: accelerating the inclusive hiring of excluded youth; unlocking jobs in sunrise sectors; enabling self-employment and enterprise growth; sustaining short term work experiences; and scaling up demand-led skilling. Our research shows that if we increase the impact of these levers and if GDP grows at a rate of 2-3%, the economy can be powered to reduce the youth unemployment rate to ±35%, enabling 9 million young people to secure employment. This is not an easy task, but it can be achieved through targeted action and collective investments. And in turn, this can further fuel economic growth and drive shared prosperity.

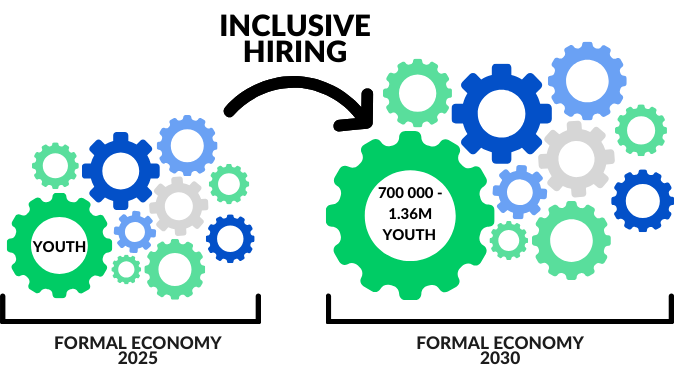

Insight: There is space for youth in the labour market and, if we hire inclusively, we can add between 700 000 and 1.36 million more young people into the formal economy by 2030

The formal economy remains a major lever for economic mobility, and the deliberate and inclusive hiring of young people into its jobs has a cataclysmic impact on their earnings potential. Young people earn on average 20-40% higher in formal economy roles compared to informal and public employment opportunities; moreover, these earnings double if the youth are in a job longer than a year.

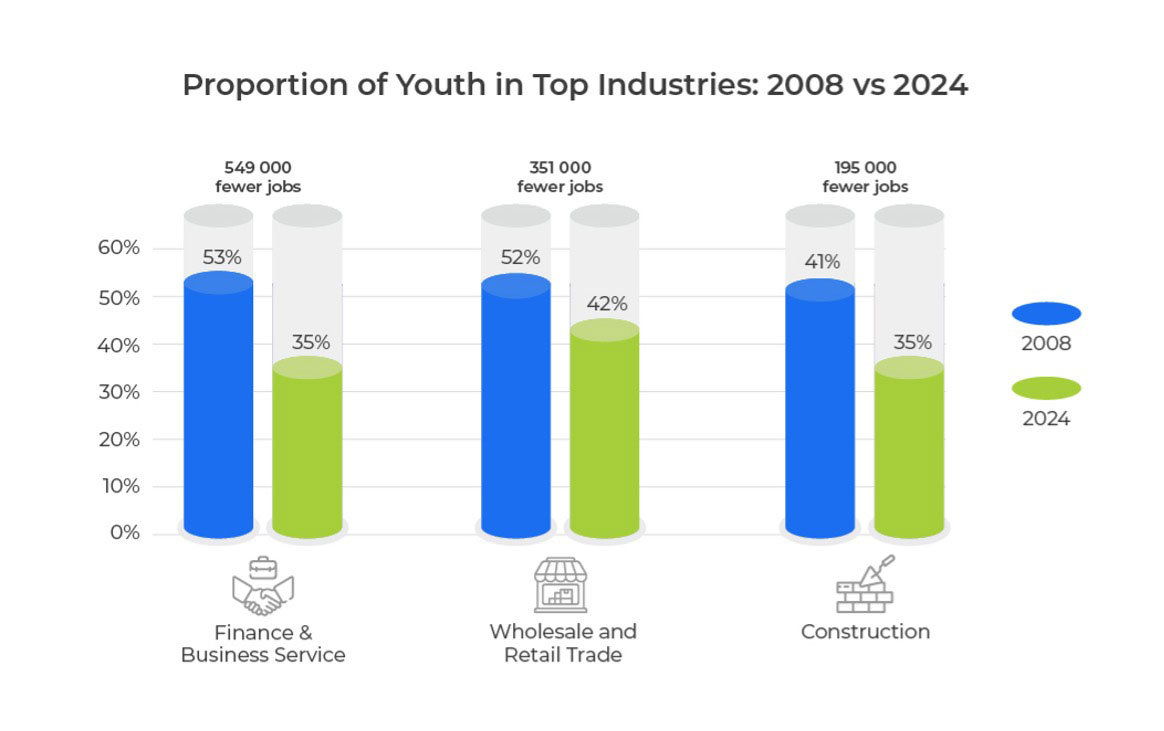

However, since 2008, QLFS data reflects that the share of working youth in the formal economy has decreased from 44% to 34%. If we drill down into the three industries that employed the most youth in 2008 (see graph below), we see that these shifts have resulted in nearly 1 million fewer jobs for young people in 2024. For example, in Finance and Business Services, youth participation dropped from 53% to 35%. Had it remained at 53%, half a million more young people would be employed in this sector. Similarly, youth employment in Wholesale and Retail Trade fell by 10%, while Construction saw a 16% decline. The biggest drop occurred in Utilities, where youth participation fell from 40% to just 22%. These trends hurt, but we know from our own experience and that of our partners, that there are many instances where sectors and employers have been able to reverse this.

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2025. QLFS Analysis 2008 – 2024.

One of the major retail banks, for example, signed over 4,000 contracts with young people over the past 7 years as part of their youth intake programme and absorbed over 1,300 into permanent roles. In 2021, the bank launched their in-house work-readiness model to equip themselves to hire and retain young people into their organisation. The TransUnion Global Capability Centre (GCC) Africa youth-focused learnership programme, is another example, and includes 20% youth with disabilities and 51% women. The company has created an inclusive employment model by allowing employees to work virtually thereby removing barriers relating to spatial exclusion and transport costs. A further example is the dynamic partnership between a major insurance company and large retailer, which has placed young insurance agents in almost 800 stores nationally. The success of the project hinges on ensuring young people live near their place of work: 1 taxi ride away – a recommendation which was taken from historical evidence and advocacy by Harambee. This approach has helped with retention, attendance, and punctuality amongst staff. The company also advances new hires an amount of their first salary to assist with up front transport costs.

It is also not only young people who benefit from inclusive hiring. There are huge benefits for businesses through incentives such as the Broad-based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) codes, Employment Tax Incentive and Skills Development Levy. Taking advantage of these incentives allows for tax deductions and subsidisation of employee training. A strong BBBEE score also increases competitiveness by granting access to state funding and public tenders and easing the process of obtaining licenses in certain sectors. Yet many organisations, specifically small and medium-sized enterprises, struggle to capitalise on these incentives, largely because there is no clear roadmap on how to access them. To support these businesses, Harambee has developed an incentives guide to raise awareness of the various incentives that exist in the ecosystem.

So, if a lot more employers modify hiring practices to be more inclusive – by engaging inclusive work readiness programmes, breaking down barriers around transport costs, and easing access to incentive schemes – we can shift the youth unemployment needle by 5-10%. This would enable an additional 700,000 – 1.36 million young people to access employment by 2030 (taking no jobs away from non-youth). Top youth-employing industries such as Finance and Business Services, Wholesale and Retail Trade, and Community and Social Work, in particular, have a role in intentionally shifting the share of entry-level roles to young people.

The fundamental structure of the economy has not changed so drastically since 2008 that it now requires a completely different mix of age and experience. There is space for youth in the economy, if we hire inclusively and actively look for opportunities to hire them.

Insight: Targeted support in high growth sectors can drive economic expansion and create between 200,000 and 375,000 jobs by 2030 reducing youth employment by 2–3%.

Over the next 5 years, the World Economic Forum Jobs of the Future report anticipates 78 million more jobs will be created globally, resulting in a 7% increase in global employment. There is opportunity for youth in the economy, particularly in sectors that have a high potential for growth and labour absorption – those like global business services (GBS), digital, tourism and the green economy.

Technological change is one of the biggest drivers expected to shape the global labour market, providing significant job creation opportunities in the digital and GBS sectors, amidst advancements in AI, information processing, robotics, and automation. South Africa’s GBS sector has experienced a 421% increase in employment from 2015-2023, a stark contrast to employment in the over-arching Financial Services and Business Sector that GBS falls under, which grew by a mere 23%. With GBS expecting to produce 500,000 jobs by 2030, the growth and opportunity in this sector is tangible. Furthermore, this growth drives the creation of jobs that youth can easily access. To meet this demand, skilling initiatives need to be accessible so young people can take up these opportunities. An example of this is the Dundee Digital Skills Hub in Kwa-Zulu Natal. By leveraging GBS sector growth, work-integrated learning models and remote work capabilities, the hub has successfully created several jobs in the rural economy. To date, the hub’s pilot programme has trained 14 participants, transitioning all 14 into business specific training and employment.

Tourism is another sector that has significant growth potential, currently supporting one out of every twelve jobs in South Africa and experiencing a 7.3% growth between 2023 and 2024. This sector needs a large workforce across a variety of semi-skilled and low-skilled positions to keep ticking, and with the number of visitors to South Africa increasing by 5% between 2023 and 2024, it is an ideal entry point for young people. We have seen the potential of this sector on SA Youth, where in 2024 the Department of Tourism placed close to 2,000 young people in jobs around the country. These placements included work in game and nature reserves, museums, and lodges.

Within South Africa’s green economy, demand opportunities in the next five years lie in renewables, specifically solar PV (both large-scale and small-scale commercial and in state utilities) and wind with associated battery storage; energy efficiency auditing; installation, repair and maintenance (IRM); and agriculture and agro-processing. Manufacturing, recycling, and upcycling also hold potential. Moreover, it is estimated that unskilled jobs will account for 40% of the new jobs that will be created in this sector. While job entrants may have access to the necessary training and upskilling for career and salary progression, this will be influenced by factors such as job stability, safety, and wages. To fully unlock these opportunities, public-private partnerships are vital to build a sustainable sunrise sector that meets acceptable quality and safety standards, provides decent work standards, and encourages organisations to upgrade or formalise their workforce capacities. For example, Nepoworx, in partnership with Harambee, has launched a Skilling and Work-Readiness Programme focused on solar installations. The initiative will support 120 young South Africans in obtaining the industry-recognised Solar PV Greencard accreditation and targets both NEET youth and small business owners, with the aim of promoting safety and quality assurance in the sector while empowering young people. Such collaborations ensure participants are well-positioned for long-term success in the energy sector.

There is still a need to develop policy and regulatory frameworks to facilitate growth, most urgently in the green economy, but if these sunrise sectors are supported to expand, they can add an ambitious 50,000 – 75,000 youth jobs per year over the next six years – creating an extra 375,000 youth jobs, and decreasing youth unemployment by 3%.

Insight: Key policy changes and driving youth to use SMME and platform partners that de-risk their entry into self-employment can enable between 450,000 and 900,000 more youth to get jobs by 2030. This will reduce youth unemployment by 3-6%.

South Africa’s informal economy is unnaturally small, fragmented, and too risky for youth to enter. Although micro-enterprise growth is often lauded as the solution to job creation, systemic factors, such as a limiting regulatory environment, the legacy of spatial apartheid, crime, transport issues, and underdeveloped infrastructure, stifle entrepreneurship and make it difficult for youth to enter, and stay, in the informal economy. Moreover, the structure and concentration of South Africa’s economy means that most essential goods are already mass-produced by large firms, making it difficult for small businesses to compete. Unlike many other developing countries, where entrepreneurs typically enter the market by producing and selling high-demand goods within their local communities, the high concentration of manufacturing and agro-processing firms in South Africa result in entrepreneurial opportunities largely being restricted to retail and services, where margins are low (Philip, 2025). And yet, informal work has been shown to be a critical enabler to access other work. Evidence shows people working in the informal economy have a 5.2 percentage point higher chance of moving into formal employment, compared to those who are unemployed and not working at all.

We need to get young people engaging in informal activities as an entry point to earning and a leverage for sustained labour market engagement. At a systems level, this requires the reduction of red tape around informal economy trade, where trading licenses for example have been shown to increase the cost of informality and contribute to higher unemployment (Balde, 2024). Other interventions like increases in targeted financing and market-based support also need to be made available for early-stage entrepreneurship and micro-enterprises.

Left to hustle on their own, young people struggle to make a living with incomes remaining low and volatile. Given that informal sector employment is often work of last-resort; a strategy that prioritises value-chain-driven self-employment opportunities, particularly those that operate at scale through platforms, is key to keeping more young people active in the informal sector. This simultaneously reinvigorates township economies. Given that such partner opportunities tend to enable higher incomes and engagement over a longer duration, young people can earn an additional R33,200 – R56,400 per opportunity. Green Riders is one example that de-risks entry into the last-mile delivery sector through the provision of structured support in the form of on-the-job training, a rent-to- own financing scheme for e-bikes and a fixed term employment contract to mitigate upfront earnings risk. Through this model, individuals earn approximately R7,000 per month – some up to R12,000 – which is considerably more than the monthly earnings of the average hustler of between R700 – R900.

Other partners such as Kwanalu, Umgibe, and Spoon Money also enable youth to access markets through work readiness offerings, incubation programmes, and business-in-a-box models. Kwanalu and Umgibe support rural entrepreneurship by facilitating market linkages and providing technical skill training for youth interested in agriculture enterprises. Intermediaries, such as Qwili and Gobuddy, provide last-mile retail and sales opportunities for township youth, and de-risk market entry by enabling access to platform-based opportunities at scale. Scaffolding provided by partners like these includes market intelligence, organisational strengthening, and access to ecosystem funding. An example of this in practice is Word of Mouth whose retail e-commerce platform stimulates local trade and the flow of informal market activity. Over four years, they have trained more than 1,000 youth in e-commerce, enabling more than 400 profitable informal e-commerce businesses to be created and facilitating more than USD $500,000 in revenue for informal sector entrepreneurs on the platform.

Finally, there are large, established intermediaries such as Uber, Sweep South, and Airbnb which already have a sizeable market share and opportunities at scale, and offer access and procurement for youth into corporate value chains. In 2023, it was estimated that Uber drivers earn an additional R2.3 billion a year in income through the Uber app: an average of 57% more than their next best alternative.

SMME and platform partners that facilitate thousands of youths’ entry into self-employment, and the subsequent earnings they enable, show there is opportunity in the informal sector. If this informal sector growth is unlocked so that its total share of youth employed rises from the current benchmark of 20% to 30% (without impacting formal sector employment numbers), between 450,000 and 900,000 more youth will get jobs by 2030. This means a drop in youth unemployment of 3-6%.

Concluding Remarks

A decade of concrete impact by Harambee and millions of data points have charted a way for us to shift the dial on youth unemployment. If each of the levers above are pulled and by following the lead of inclusive employers, and the range of SMME partners and youth-centred platforms, we will do what President Ramaphosa has called us to do: hire youth, hire them into jobs that make sense for them, hire them into sectors where there is much promise for future jobs, and support them to start their own businesses so that, one day, they hire others.

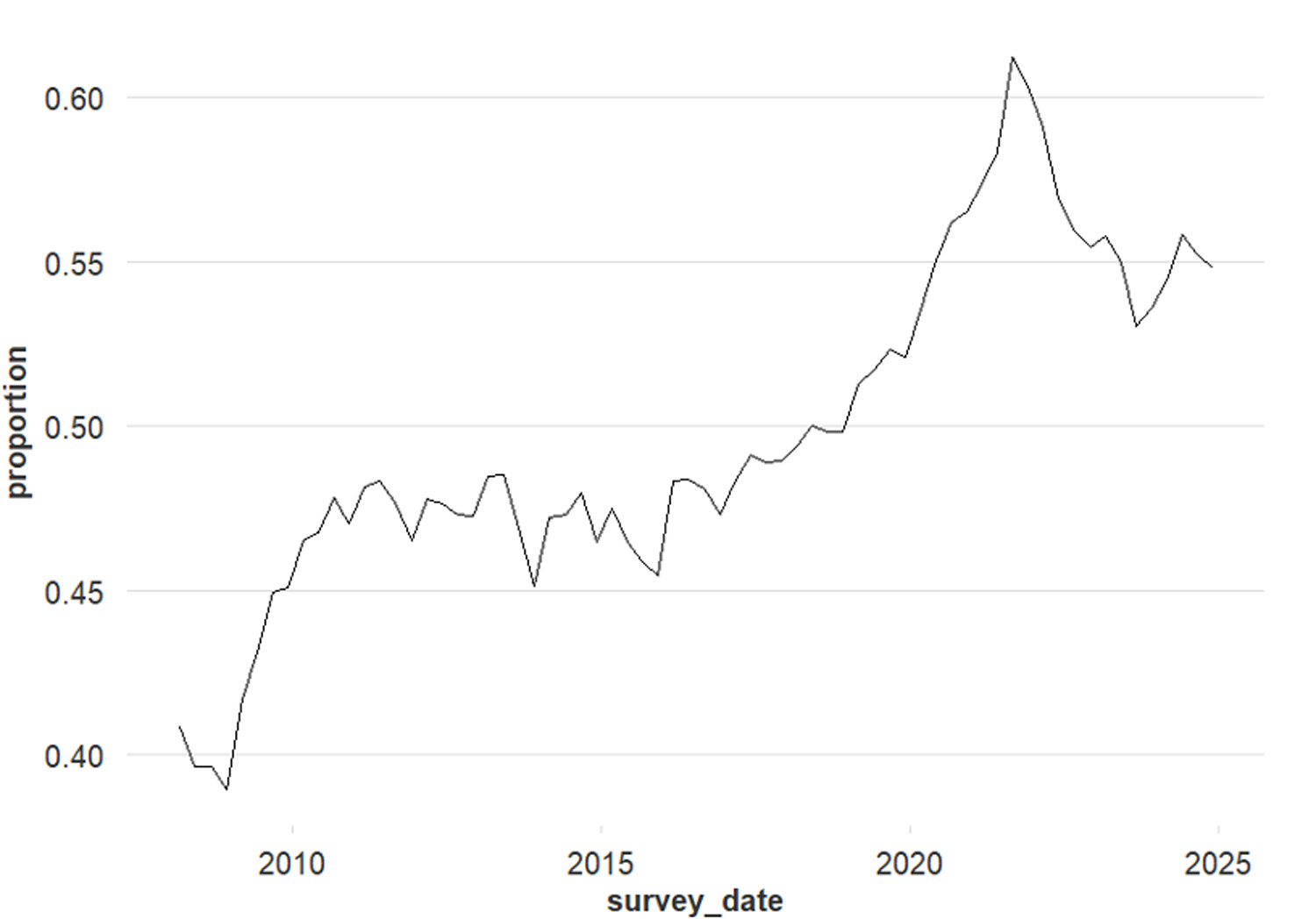

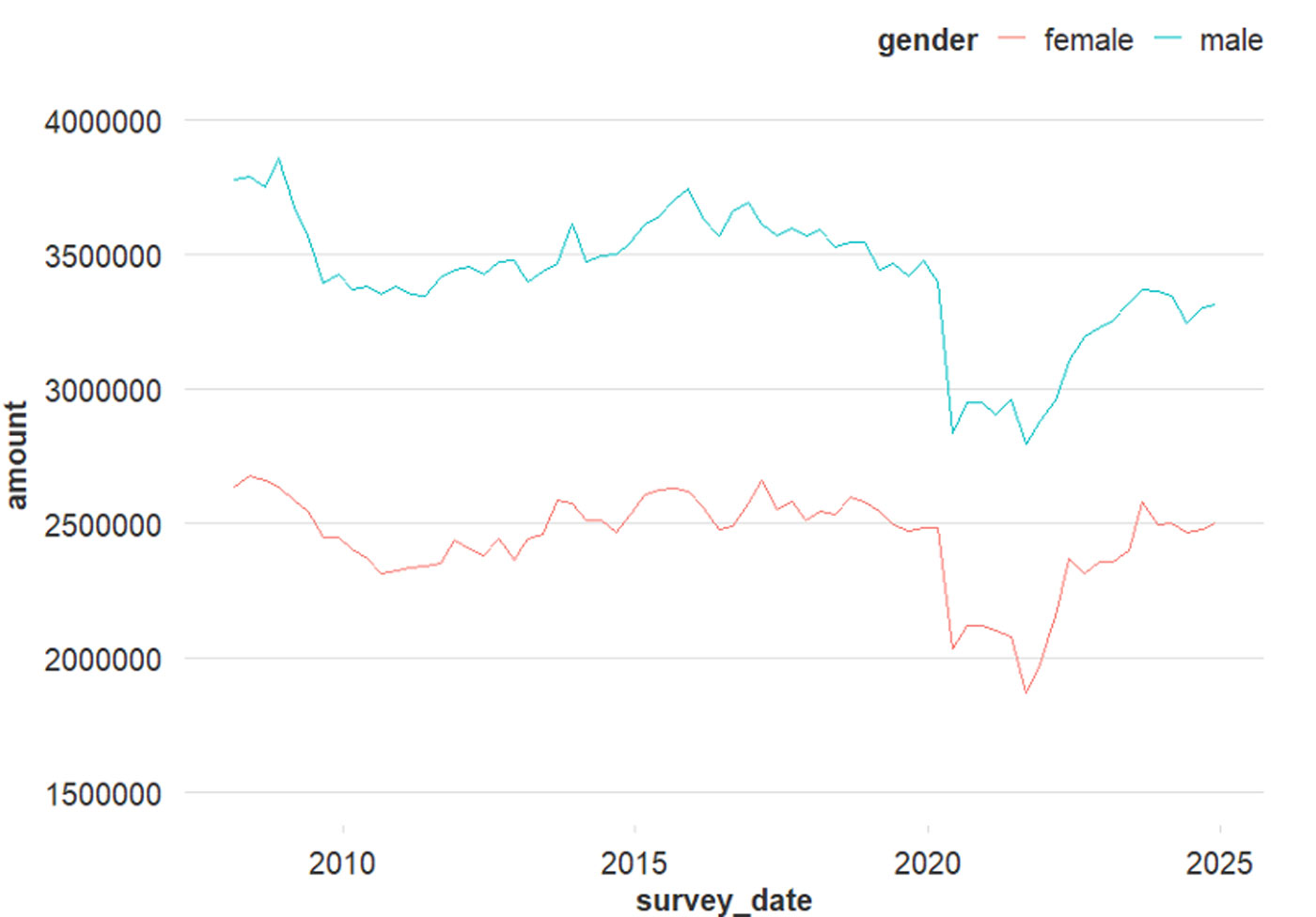

While the QLFS for the last quarter of 2024 showed no substantive change in employment levels, it did show a substantive need for big and bold action. The unemployment rate for youth aged 18 – 34 years lingers at 55% – a seemingly new, ‘structural’ post-Covid norm. Compared to a decade ago, this is a decline of 9%, or between 200,000 and 500,000 less youth actually working. NEETS (youth not in employment, education or training) aged 18-34 years are up from 8.6 million to 8.8 million compared to the same quarter in 2023, and both male and female youth employment rates remain mostly flat.

At 45%, the proportion of young people moving into the labour market has, in other words, stalled. To get the wheels in the labour market turning again, Harambee’s five youth employment levers need to be pulled. Seen through an inclusive employment lens, the QLFS contains clues as to how – and where – to do this.

The QLFS show that, in Finance – one of the top youth-employing industries – there has been a large increase in employment with 179,000 more jobs, compared to the previous quarter. This has unfortunately not extended to other youth-employing industries such as Trade, and Community and Social Services, where the jobs recorded this quarter have decreased slightly but, compared to a year ago, these industries have contributed significantly to overall employment. A net gain of 192,000 jobs in the formal sector shows movement and elasticity: a strong sign that there is space for youth in this sector, if they are hired intentionally and inclusively.

We know that the formal sector dominates the economy and the QLFS confirms this, showing that it accounts for 68,4% of total employment. Formal jobs have grown by 90,000 over the past quarter compared to 34,000 additional jobs in the informal sector but, again, where there is movement, there is possibility. While we know these job gains in the informal economy are not going to enough youth, they still indicate potential for growth in the sector. With the steadfast movement of youth towards SMME and platform partners that facilitate their entry into self-employment, we can ensure they take their place in the informal economy.

A stalled youth employment flow and a new, stubborn, ‘post-Covid’ labour market are undeniable dynamics of the South African economy but the solutions to displacing these are right in front of us, with the evidence and data to match. Boldly committing to shifting business practices and working with government on new and enabling structures will change the systems that keep youth employment down, for good.