SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

Old world, young Africa, the NY Times published last week—and on its heels, the same publication outlined the desperation of South African youth trying to look for work. These two pieces simultaneously outline the promise and the peril of the youth dividend in Africa.

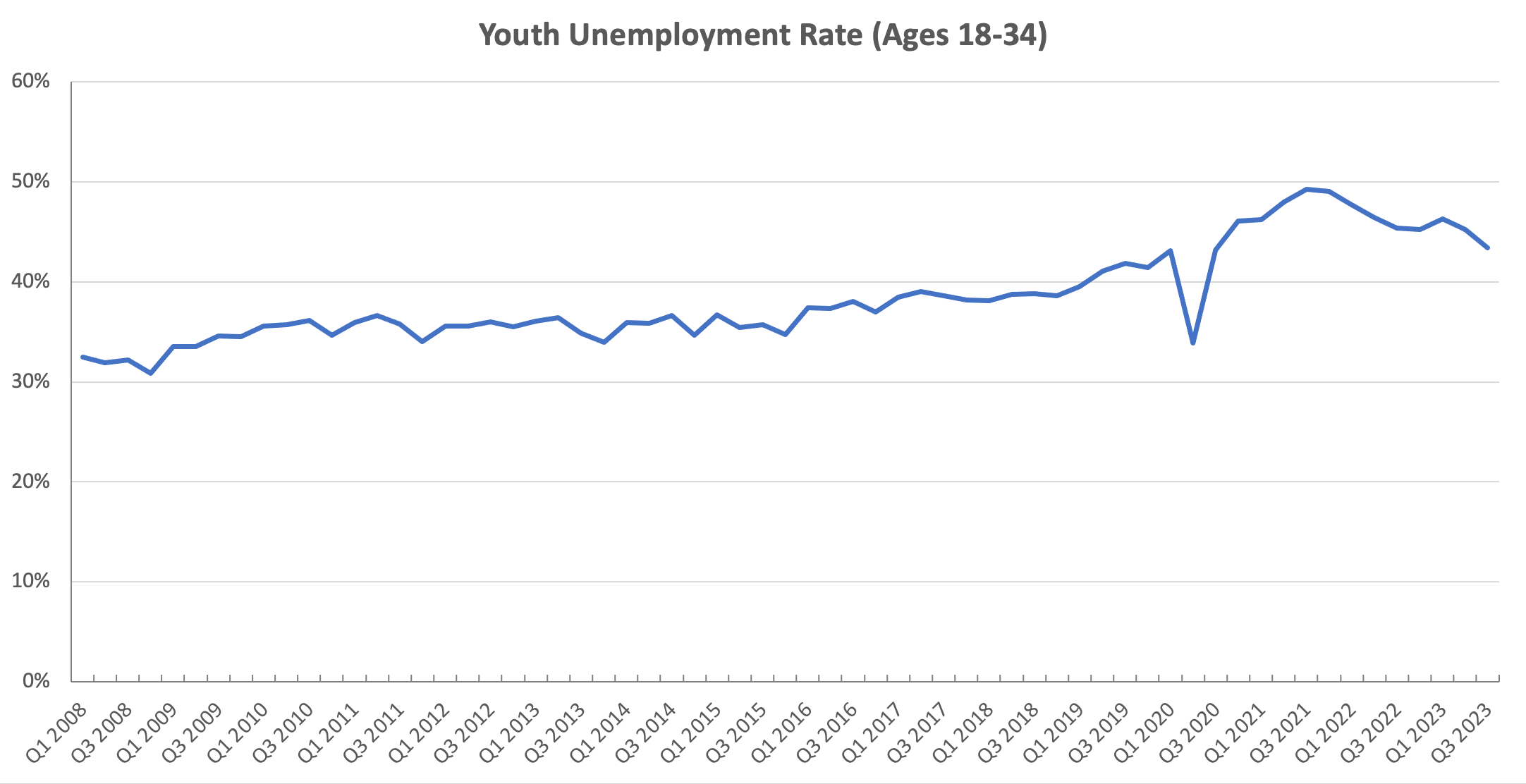

This week’s Quarterly Labour Force Survey sheds some positive light on the unemployment crisis—but the glimmers of hope need to be interpreted with caution, and the urgency to double down on this has never been greater.

As the QLFS is published this week, we must set it in the context of another recent publication from the national statistical office: the census. These two data sets together paint a full picture of the challenge on youth employment. From the census we learnt that the total population of South Africa grew to 62 million people, a 20% increase over the 2011 census. The shape of this growth provides clues as to what we can expect. While our birth rate has been relatively stable for about 30 years at around 1 million per year, we’re living longer and longer. The youth population increased since 2011, but by a smaller margin. And this growth for the youth population might very well be lower still over the next decade. This is an important backdrop for looking forward as we think about employment.

If the census confirms that the size of the youth wave entering the labour market each year will continue at its current magnitude, the QLFS tells us what is likely to happen to them if we don’t intervene. At 8.57M NEET youth according to the latest QLFS release–our youth unemployment challenge dwarfs every other nation’s. Despite small positive trends in employment quarter-on-quarter, more than four in every ten young people were not in employment, education or training. However, the insights Harambee and our partners have compiled over more than a decade of working on this problem tell us what we can do about it. As of July 2023, Harambee and our partners have gained line of sight into over 1M work opportunities. Many of these we created; others were discovered, facilitated, and reported via our platforms. These opportunities represent one million doors into work for young people, but just as important, they are one million windows into the realities young people face, the barriers they encounter and the solutions that actually work. This insight, much of which has been shared in previous reports, underpins the partnerships we have forged and solutions we have designed together. When deployed in a coordinated way through pathway management, these solutions make a seemingly intractable challenge addressable.

Together, these three sets of data – the census data and projections, QLFS trends, and Harambee’s own insights – point to a roadmap for how we can reverse the trend of increasing NEETs with concerted and collective action. In this edition of Breaking Barriers, we outline three specific sets of insights from our 12 years of experience that, if leveraged, can serve to reverse the trend of increasing NEETs.

Reversing the NEETs crisis requires widespread adoption of pathway management

Of the roughly one million people exiting education annually and trying to enter the labour force today, just 20% of them find employment within that year (QLFS, Harambee analysis). We know that these are the young people with advantages – they hold tertiary qualifications and have networks into the economy, often from having attended a higher-resourced school. They have the means to afford job searching, and most of the jobs they secure are in the formal sector, with relatively higher pay and stability. The social and geographical dimension of these advantages mean that they tend to compound over generations.

Another 20% of this one million will eventually find a job, but this job is more likely to be in the informal sector, or a short-term position in the formal sector—and it might take years of navigating a maze of often confusing and broken systems, temporary contracts, internships, or public works gigs, and/or micro entrepreneurship and hustling efforts to find this work. For this group, their ability and momentum through the maze is significantly affected by dimensions of exclusion—gender, location, age, completed education and school quintile.

The remaining 60% of the one million is likely to remain outside employment, education, or training—at risk of becoming permanently disengaged. We know that those who have failed to find any form of work by the age of 30 are vastly less likely to secure a first role after that point. This gives us an intervention window to focus on to keep this segment engaged while we work to shift the ratios.

The 1M+ opportunities created and mapped by the coalition to which Harambee belongs is that pathway management works. It breaks down systemic work-seeking barriers around data and transport costs, providing line of sight to a work-seeker’s first and next opportunity. Our research shows that engaging with work opportunities, with support and encouragement, has a positive impact on employment outcomes: those spending three days on the SA Youth platform in a given period have a 10% higher chance of employment than those spending just one day. Pathway management also enables geo-spatial matching, which directly reduces work-seeking costs. In one example, the Department of Basic Education (DBE) School Assistant programme used the location-based matching component of the SA Youth platform, contributing to an average transport cost saving of R236 per month – equating to over R1 billion in savings over the programme’s four phases. This is money in the pockets of eager and desperate work-seekers, while the programme itself provides critical skills and keeps this group of youth engaged. In 2022, over 2.3 out of the 3.5 million youth under 25 years old expressed a desire to work. But among those who actively search for employment, a staggering 81% have never worked before. Thus, work experience programmes that absorb this “desire” to work (not just train) are an important component of the pathway management approach. These types of programmes can come under fire for not leading to immediate transitions–especially in the face of few formal sector jobs. However, they provide young people with work experience, which we know results in higher employment outcomes. They also provide a wider economic impact, with research on the DBE School Assistant programme reflecting a 15.4% sustained increase in spending amongst youth, benefiting local trade and retailers (Bassier & Budlender, 2023).

With a coordinated partnership between business, government, and civil society, we can amplify these gains. By supporting pathway management as a concept—breaking down barriers in the channels of entry-level hiring and supporting work experience of all kinds—we can not only stop the hemorrhage of youth out of the labour market but give them both hope and options in their most productive years, allowing them to more easily enter and stay in work.

The 1M+ opportunities enabled took our coalition 12 years to generate and map. But as we’ve seen, even as the shape of our population shifts, the challenge keeps growing: if we simply sustain that pace, we will keep on treading water and not shift the economic participation of this generation of youth. We now need to pull the critical levers that make a dent in the problem with greater force and coordination than ever—across business, government, and civil society. We need to embed a system that can deliver employment outcomes that matter, at sustainable scale and much greater pace.

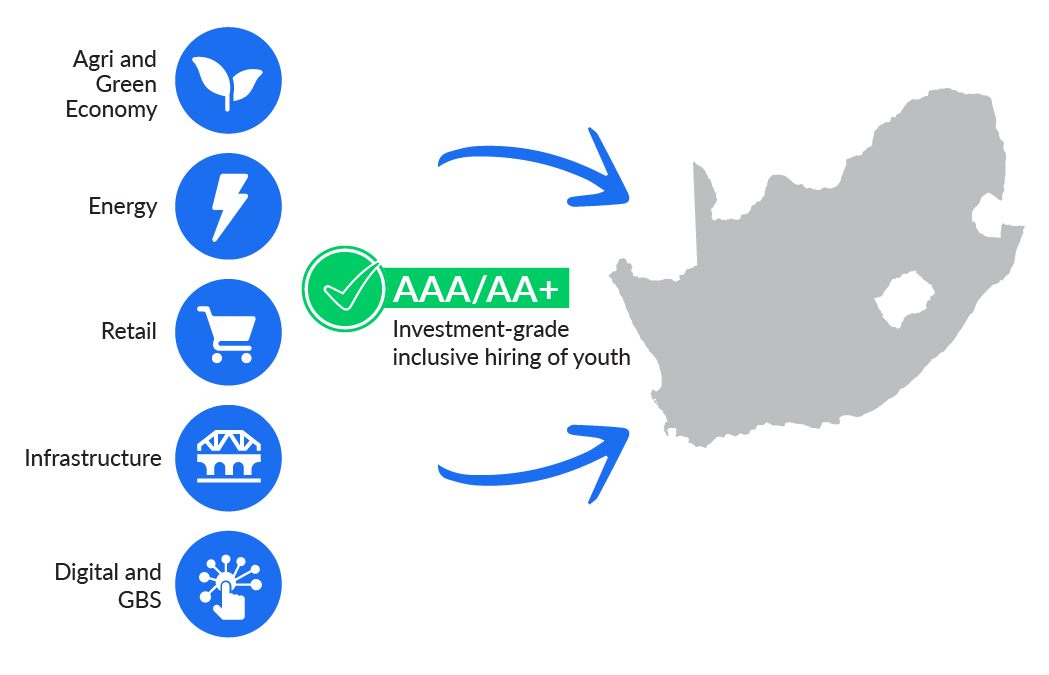

“Investment grade” inclusive hiring hinges on shared understanding and sector-based facilitation

“Taking a bet on youth alone” is insufficient, in the words of Cheslyn Jacobs, Chief Commercial Officer at Tyme Bank. We need to invest in youth, not take a bet on them, because betting on youth suggests that it’s a gamble that can go either way, whereas the investment lens forces us to apply rigour and focus to ensure a positive outcome. Tyme Bank’s own success–of over 8M+ customers and counting–has in fact relied on this explicit investment into youth as a driver of growth and success.

Harambee’s 12 years of experience and 1M+ placements suggests that inclusive hiring works. However, we’re calling for investment grade inclusive hiring if we are to reverse the NEETs trend. This calls for a shared understanding of what inclusive hiring means across the stakeholders who comprise the players in the economy – or “S.A. Inc” , as well as a shared agreement and commitment on what it will take. This has been seen in the often celebrated Global Business Services (GBS) sector. where years of coordination has built a shared understanding that inclusive hiring (of youth, women, people with disability, and of those from excluded socio-economic backgrounds) will help jointly drive the sector forward. And indeed it has–in fact the sector’s commitment to 30% inclusive hiring has been consistently exceeded.

The GBS sector has been a first mover in this regard, using inclusive hiring at a sector-, industry- and country-level to solve a business problem. Between 2010 and June 2023, the sector created 128 222 jobs and achieved over $2 billion in export revenue. In the first half of 2023 alone, we see the impact of inclusive hiring as an explicit sector strategy with 8,388 new jobs created of which 91% were for youth, 37% (3,109) were inclusive hires and 62% (5,200) went to women. The net effect for the sector was realising R1.3 billion in export revenue. These outcomes hinged not just on the hiring itself, but on conscious investment in the work-readiness and integration of new workers into the workplace. Without exception, those investments paid off.

Critically, the SA Youth platform is a proof of concept for how inclusive hiring can be done at scale, with free, easily accessible, and well-matched youth for entry-level hiring needs. Of the 1 million work opportunities that have been reported on the SA Youth platform, 70% went to women–compared to the 42% of young women in the labour market. Of the 1M, 40% went to those < 25 years compared to the labour market benchmark of 18%, and there is greater representation of youth from quintile 1 schools vs. national employment dynamics which favour those from well-resourced quintile 5 schools.

The above composition data from the SA Youth platform holds true for public employment programmes, but importantly, for young people reporting private sector jobs on SA Youth–particularly in financial services, business services and retail. These sectors combined represent two-thirds of the national youth jobs. SA youth’s biggest employers include national retailers like Shoprite, Pick n Pay, Foschini, Mr Price Group, Massmart and Clicks Group, as well as financial services employers Sanlam, Standard Bank, FirstRand, Nedbank, and Capitec Holdings.

With coordinated effort across SA Youth and SA Inc. we can make inclusive hiring at the entry level easy for South Africa’s top employers. This can happen both for high-absorbers of today—such as Shoprite, Bidvest, Sanlam—and for the sunrise sectors of tomorrow, like GBS and digital, which while small today compared to the size of the problem, will continue to drive growth. In all these sectors, coordination is needed between business and sometimes coalitions of stakeholders around challenges like shortfalls in demand-led skilling and regulatory bottlenecks. In the digital boom, even fresh graduates need support transitioning into the workforce, and the solar boom needs targeted skilling. Our experience shows that, left to its own devices, even dominant and growth markets do not automatically clear quickly enough.

With shared understanding, collective agreement and coordinated action, we know that we can make a sound investment in SA Inc.’s biggest and best asset: its youth, for the benefit of SA’s youth, for the economy, and for our society as a whole.

Figure 2: Investment grade inclusive hiring of youth through SA Inc and SA Youth

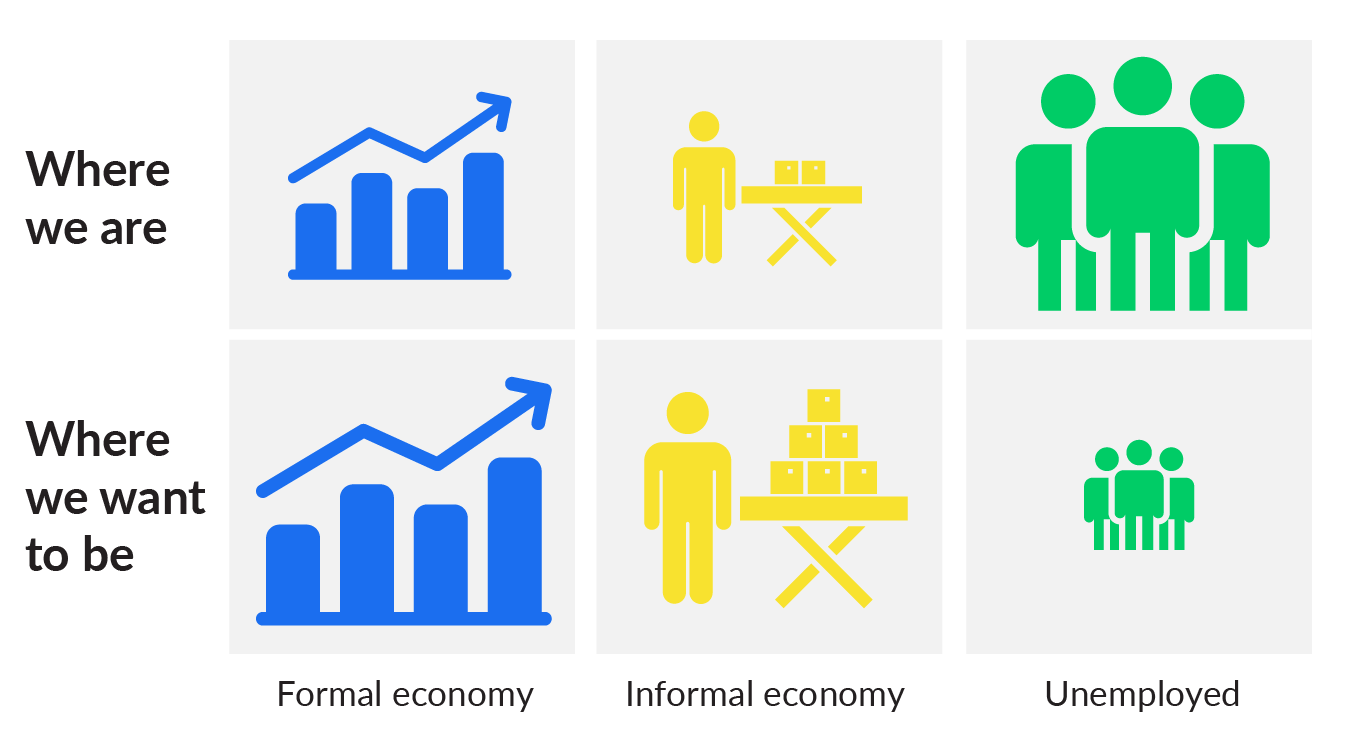

To move the needle on unemployment, we need to shift the contours of the economy itself, actively growing the informal sector.

For historical and structural reasons, the SA economy has a very small informal sector when compared to other developing economies. Comparable economies absorb 45% into formal sector employment, 45% in informal employment and have 10% in unemployment. South Africa’s situation seems abnormal in comparison, with 50% in formal employment, only 16% in informal employment and 36% unemployed (Bhorat, 2022).

The informal economy, while an obvious pathway to economic mobility in many other economies, remains harder for youth in South Africa. Incomes are low and volatile, and options are limited. South Africa’s economy–by design–has been biased towards the formal economy, potentially minimizing alternate pathways into economic inclusion. We need to scaffold youth into opportunities and support businesses to see this as a viable investment.

Data from the National Income Dynamic Survey (NIDS, Cichello and Rogan, 2017) suggests that income from formal jobs is of unparalleled importance to national income. Formal sector employment earnings comprised over half the total per-capita income received by South African households in 2008 (Cichello and Rogan, 2017). This is supported by Harambee’s own data, which suggests that youth in formal sector wage jobs earn on average, R3,000-4,000 per month (Harambee income survey, 2023), whereas informal sector jobs earn less than half that amount on average–and often skewed significantly by gender, with women earning far less, facing significant time-poverty and other barriers.

But the informal sector, despite constrained size and relatively small impact on national income, has an outsize role in terms of addressing poverty. As Cichello and Rogan, point out, not all income is created equal. The poverty-reducing effectiveness of each income source–derived by calculating the ratio between its share of poverty reduction and its share of income–suggests that social grants reduce poverty by more than 3x their share in total income. They also highlight that that informal wage employment does so by nearly 2x–suggesting that it can have a disproportionate impact on addressing poverty alleviation.

This segment is also an untapped growth sector estimated at over R600 billion in value, and is rife with opportunities for young people. QLFS data from 2012-2023 suggest that male informal sector employment increased by 44% over this period while female increased by 13% and off a much lower base. Informal sector employment is also significantly lower for youth, relative to the size of the youth labor force and youth population. This is at least in part because the highest risks in entering the informal labour market fall squarely on the most excluded. We need to scaffold young people’s entry into the informal economy—that is, buffer youth from the inherent risks (precarious income, volatility) that exist in the informal economy, and that often turn both young people and even businesses away from this potential engine for growth.

Harambee’s own experience in this space suggests that informality is a spectrum, not a status, and that young people are forced into small-scale “hustling” work often out of necessity. But with a bit of scaffolding—such as cash flow support, market intelligence on how to grow customers, and advice on financial management—they can grow into gig workers and micro-entrepreneurs. However, penalties for formalisation abound, and we need innovative approaches to encourage the growth in this space that supports youth with scaffolding, alongside work to replace unnecessary regulations and penalties for informality, with incentives to flourish.

Funding partnerships like the SA SME Fund–which catalyses both business and government support of township micro-enterprises–can stimulate semi-formal work & youth self-employment. We need many more such interventions across the value chain, to encourage both own-account workers as well as those that are more likely to request and benefit from traditional start-up capital. Importantly, we need different ways of financing a sector where the risks are high, and traditional venture capital and funding instruments can often serve as an impediment. The reduction of red tape for informal trading, and the unblocking of regulatory bottlenecks or informal traders, such as in the agriculture and tourism sectors could generate hundreds of thousands of opportunities.

The data tells us that the unemployment crisis is not solving itself, nor is it going to. But it also tells us we have a window to turn the corner. Pathway management at scale and pace, investment grade inclusive hiring, and unlocking the informal economy to create massively more work opportunities: these are the tools we know work, based on the evidence of more than a decade and more than a million opportunities seized by young people through our networks. The roadmap to the next million is increasingly clear.

Figure 3: Shifting the contours of the economy

The latest QLFS figures for Q3 2023 reflect a small but steady improvement in youth employment, with levels for 18-34 year olds finally reaching pre-pandemic figures at approximately 5.9 million young people employed. Whilst the 16.7 million total employed in the economy is the highest ever recorded, the youth number is still 0,5 million less than its all time high. Compared to Q3 2022, youth unemployment has declined by 1.98 percentage points and 43.37% (and the expanded definition to 53%); however, amidst a growing labour force (as reflected in the latest census), the unemployment rate and total figures are still higher by an estimated 250,000, compared to 2019 figures. This trend is also reflected in the total number of NEETs, which have also decreased by 230,000 over the last quarter to 8.57 million but is still remain above the 8 million NEET figure recorded in 2019. In terms of gender, female employment levels have reached a similar level to pre-pandemic, but males have not caught up, although the female employment rate overall remains lower than male. Considering that employment in the mining and manufacturing sectors, which are traditionally high absorbers of men, are marginally below pre-pandemic levels – this may explain the gendered impact. The unemployment rate for women is still almost 4 percentage points higher than that of males. Sectors that experienced growth include Finance, Community and Social Services, Agriculture and Construction. The largest increases in employment were recorded in Western Cape, KwaZulu Natal, Limpopo, Eastern Cape and Gauteng.