SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

This month we are taking a deep dive into the articles released as part of the National Income Dynamics (NIDS) Coronavirus Rapid Mobile (CRAM) survey. This is the second wave of results to be released from NIDS CRAM, providing an overview of the experience of South Africans during lockdown regarding unemployment, household income, child hunger, education and access to government grants.

At Harambee, we are using this data to inform how best to respond to the challenges faced and opportunities that emerge to continue our support for young people.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on employment outcomes in South Africa’s labour market, with an estimated 3 million jobs lost between February and April 2020. Less skilled workers and low-wage earners were hardest hit, and likely to lose their jobs or be furloughed (take an unpaid leave of absence from work) during the lockdown.

This pattern was partly reversed between April and June, but not enough to recover to February levels. In fact, almost 25% of those furloughed reported no longer having a job by Wave 2, despite lockdown restrictions easing.

Image Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2020

The first wave of the NIDS-CRAM results, released in June 2020, reflected that two-thirds of the total jobs lost were by women and Wave 2 suggest that women continue to fall further behind. The wage gap widened, with working women earning an estimated 29% less hourly wages than men before the lockdown, which increased to 43% less than men in June. This deepening gender wage gap is especially severe amongst the poorest 40% of wage earners. Women were the hardest hit but did not benefit from the relief provided, on account of the fact that they may have been excluded for receiving child support grants. Despite the fact that women represented 58% of those who lost their jobs, only 41% of beneficiaries from the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) and COVID-19 Social Relief Distress Grant (SRDG) were women. This was likely because the COVID-19 relief grant cannot be held with another grant such as the Child Support Grant, which effectively penalises unemployed women who are also the main caregivers to children.

Women bore the brunt of closures of childcare centres, with more than twice the number of women reporting that childcare in June prevented them from going to work.

Action Steps

Image Source: South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), 2020

In response to the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic lockdown, South Africa’s government identified a package of relief measures to expand social protection systems. This included a COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress Grant (SRDG) for unemployed individuals, and a Child Support Grant (CSG) ‘per grant’ top up of R300 in May and ‘per caregiver’ top-up of R500 from June onwards. The good news is that the COVID-19 relief grant brought millions of previously unreached individuals into the system, and the grant reached the most deserving – of those who received the grant, the majority were in low-income households. The grant was also successful in reaching those who had fallen into poverty during lockdown, indicating the grant’s success as an interim relief measure. Whilst the study found that both the ‘per child’ and ‘per caregiver’ top-up of the CSG was progressive, the ‘per child’ top-up was marginally better because more than two-thirds (66.8%) of CSG-receiving households receive more than one CSG.

Although the government’s expansion of social assistance is due to come to an end in October 2020, continued labour market conditions that disproportionately burden vulnerable individuals may require policymakers to consider alternate policy measures:

Action Steps

Image Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2020

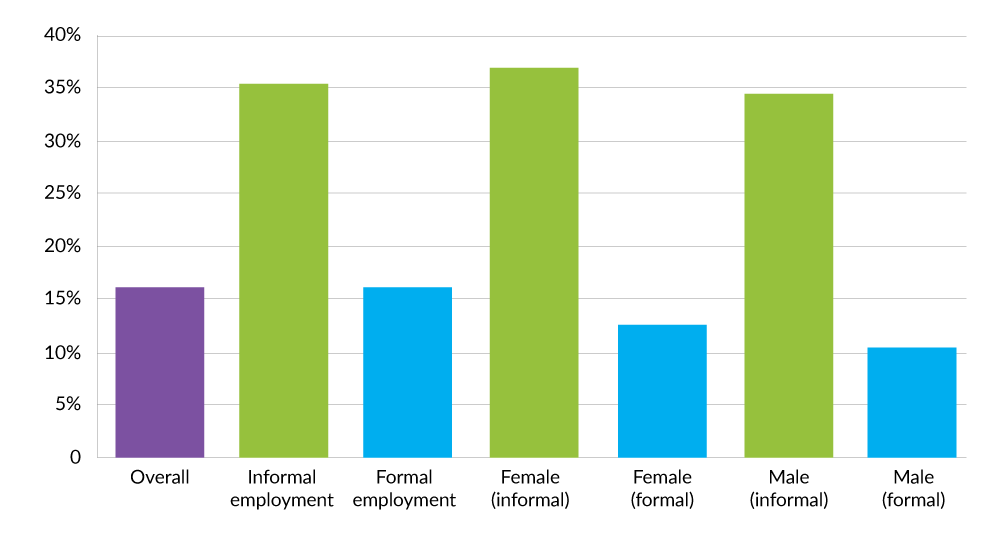

Unlike the rest of Africa, where 86% of all workers are in the informal economy, only a third of South African workers are employed informally. The small size of the informal economy is partly attributed to high barriers to entry and high reservation wages among the unemployed. Informal workers in South Africa and the world over bore a disproportionate burden of the COVID-19 lockdown and social distancing measures. Apart from informal workers who provide essential goods and services, these regulations meant a loss in livelihoods for informal workers, especially those who rely on day-to-day earnings. The rate of vulnerability to income loss for formal workers was lower, largely because they are cushioned by various contractual agreements. Job losses were higher among informal (36%) compared to formal workers (11%), with informal workers in urban areas being more vulnerable when compared to those in rural areas.

Action Steps

Figure 1: Proportion of employed South Africans who became unemployed in wave 2

TOLL-FREE SUPPORT LINE

0800 72 72 72

Call us for support.

WHATSAPP CHATBOT

Say “Hi” to +27 87 2405 122

Get daily tips and challenges.