SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

Young South African women are disproportionately represented on our platform, SA Youth – evidence of their competence, their readiness to work, and their tenacity. SA Youth is 66% female, and our nearly one million enabled placements are 68% female. Together, these facts suggest that not only do South Africa’s young women remain optimistic and resilient despite the odds they are dealt, but when we break barriers for them and address the systemic disadvantages they face, they seize the opportunity readily. Harambee’s experience suggests that this creates immense value for organisations, communities, economies, and society as a whole.

More educated, more tenacious and less employed.

Across the board, women outperform their male counterparts in education with younger cohorts attaining higher levels. For every 100 young men in South Africa under 35 with a matric, there are 112 young women with the same. Even starker, there are a staggering 50% more young women than young men with degree-equivalents or higher.

This is a generational win for women. Younger women are better educated than their female seniors as well as their male peers. For the population over 35, fewer women than men hold matric (5% fewer), and fewer women than men hold degrees (15% fewer).

For all these gains, however, women still make up less of the labour market across all age cohorts and where they are working, they on average earn disproportionately less than men within the same job family.

This gap between levels of education and employment has not dented women’s tenacity in seeking work. In fact, data from our network seems to show that women have even greater tenacity than men at lower levels of educational attainment: the SA Youth network continues to cater to those for whom barriers are higher and harder – 48% of those registered on SA Youth have a matric, and only 17% with a higher degree. Among this cohort, women and men are equally represented among high performers at matric (those who achieve 60% or higher in pure maths). But for those who just pass matric (50% or lower), there are 2.5x the number of young women raising their hands for employment.

Examples from the SA Youth network indicate that when they are given an equal opportunity, women seize it. In the Department of Basic Education (DBE) school assistant programme, 70% or more of the SA Youth network in these roles are women, versus 65% representation in the overall SA Youth network. This is an example of a programme where many of the traditional barriers to women’s employment were broken down by design: fewer educational requirements, placement close to their homes, a relatively safe working environment and mandated equal pay. Though temporary, these roles have proven to be a stepping stone for many women, such as Tebogo Gaborone.

Tebogo was born in 1998 and grew up in Soweto in Gauteng. She currently lives in Orlando West, a suburb of Soweto. Tebogo was not able to matriculate due to becoming a young mother and having to support her family, but she always dreamed of becoming a beauty therapist, enrolling at a local beauty school to learn skills. Tebogo found out about the teaching assistant opportunity through SA Youth. She says the experience taught her entrepreneurial and communication skills which enabled her to start her own business. She is currently working as a lash technician, doing eyelash extensions from home, and hopes to have her own salon one day. She attributes her progress to tenacity, advising young work seekers to apply for jobs every day, learn a new skill every day, and never give up.

The flexibility of gig and platform work does not automatically work for women—yet.

Work seekers like Tebogo have sought to transfer skills from a formal but temporary contract, into entrepreneurship, and they are not alone. Harambee’s decade of experience with young people suggests that the future of work is already here for many: there are fewer jobs of any kind and far fewer long-term ones for young people. With South Africa’s economy projected to grow only 0.3% this year, this will persist for the foreseeable future, making a mix of contract, gig-based and informal work the norm. It is an economic reality already familiar to many young women who for centuries have been juggling multiple, informal economic roles inside and outside the house, and doing work that is also unseen and often unpaid.

However, women’s historic work-juggling skills do not translate into an advantage when it comes to today’s gig jobs and contract work. Harambee’s research shows that men earned 1.4 times more in hustling engagements, while simultaneously working more hours – at least 10% more hours per week. Over and above gender wage disparity, this reflects two additional factors. The first is the disproportionate burden of unpaid care that women face (such as housework and caregiving) which reduces the time available to look for and participate in paid work.

Second is the host of barriers that affect all young people, but hit women particularly hard–even in growing sectors. For example, the delivery driver sector is a growing industry, between 2017 and 2019 alone, for example, the number of new 50cc – 250cc motorcycles in the market more than doubled. But even in these growing sectors, roles remain difficult to access due to bureaucratic licensing requirements; difficult to sustain because of their precarity, and rife with opportunistic exploitation by dangerous actors who saddle young people with more costs than income.

The levers to unlock and safeguard these opportunities look different to those in the formal economy. Firstly, expecting young people to just start, run and grow businesses without some scaffolding is unrealistic. Our research suggests that incomes earned by young people without support are low (on average R700) and very precarious. But this can be mitigated by providing initial market intelligence and a degree of stability around employment contracts and wages as Harambee partner Green Riders has shown. For example, Ayandiswa is a 28-year-old female Green Rider, who was born and raised in Uitenhage, Eastern Cape and moved to Cape Town, Western Cape in her early teenage years. Before joining Green Riders, she was unemployed following the end of a work contract. She therefore was dependent on the support of her family where possible, while pursuing her own hustles on the side. For Ayandiswa, Green Riders has been a smoother entry into the labour market. Since joining the delivery team she has a sense of community and belonging, which she articulates as a great honour as it feels like “being part of a great movement”.

Secondly, effectively supporting the growth of SMMEs and intermediaries that in turn employ young people requires investment, capacity building and targeted support. SMMEs cannot easily grow and absorb the jobless, without both patient capital and support to onboard and retain excluded youth.

Finally, the scalability of these SMMEs themselves may be tested given the macro-economic dynamics of South Africa. Here’s where innovative and catalytic funders like the Jobs Fund and other private philanthropies continue to play a critical role not just in providing capital, with a good dose of patience, but also in insisting on metrics of job creation that are realistic and shine a light on exclusion.

When we design doorways into male-dominated growth sectors, women run through them

The Installation, Repair and Maintenance sector is growing in demand in South Africa, as those of us waiting for installation of solar panels) can attest to. Amid a well-documented artisan crisis, the fact that only 3% of plumbers in the industry are licensed women should be a call to action. The good news is this is an addressable gap as Harambee’s participation in a partnership funded by the UK Government’s Skills for Prosperity shows. We outlined ambitious targets for female participation in our skills and work experience programme, training and placing over 50% of the earning opportunities for women alone. This was achieved through a coordinated effort between the industry body, Institute of Plumbing South Africa, and partners including the National Business Initiative, Blu Lever, and Harambee, to promote “Gender and Social Inclusion” among partners.

Our learning: the need for gender advocacy is greater than anticipated and must be designed into the entire project value chain (among young people, employers, sector bodies, training institutions). This is especially true when it comes to getting employers to offer opportunities to women for the work experience component of the programme, leading BluLever Education to launch the #Womenontools campaign to highlight the benefits to employers of gender equity and social inclusion (GESI). Initial indications show a correlation between employers attending training on how to work with apprentices that includes GESI content, and fewer adverse GESI incidents. Training of all young people on GESI is key and this becomes more powerful when the implementing partner takes ownership of the content and incorporates GESI into the entire programme. Support for young people in the programme is key and ideally should be allocated a dedicated resource that is not the same as the person supporting employers. This will ensure that candidates have a clear line of communication for GESI issues and ensures young people have someone advocating for them when there are issues in the programme. Further work must be done at the industry level. Developing policy and funding mechanisms for maternity benefits in technical training programmes, for example, are a blind spot for many organisations and HR policies are a key lever in reducing drop-out rates.

As well as formal mechanisms, our experience suggested that more young people were more likely to join and stay in the programme if they had successful role models to follow. Telling stories of success remains a key element of the programme such as that of Valecia Sambo, a previously-unemployed participant on the entry-level NBI programme who says she didn’t expect to become an entrepreneur. As well as foundational plumbing skills, with the ability to progress to more specialised skills after qualification, the programme also gave her a grounding in entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial training. “I learned throughout the programme that I had a future as an entrepreneur. I didn’t know one day I would have my own company, make my own money and also empower [others] where I can,” she said.

Making achievements like Valecia’s the norm, not the exception, is possible by setting ambitious targets for gender inclusion and specifically partnering with like-minded organisations to drive execution. We can also replicate this success in new sectors that hold promise as a source of jobs for young women, like the green economy. In the solar installation sector, for instance, demand is high (solar cell imports to South Africa in the first quarter of this year alone nearly equalled the total imports in 2022), but the sector remains elusive for youth, and for young women in particular, due to unclear and expensive entry skilling and licensing requirements. As a result, the percentage of women employed in this sector is considered to be relatively low at 22%-25%, in comparison to other sectors (IEA, 2022; Trace, 2020). If we want to apply clear lessons on effective gender and social and inclusion to the growing renewable energy sector, we could start with the installation of solar panels.

The economic picture presents challenges for all young people, especially for the most excluded and for women. Our experience continues to yield reasons for investment, partnership, and optimism. Women are gaining ground in educational attainment; they are dogged in pursuing work, and hungry for opportunity in the economy’s growth spots. But higher schooling and tenacity alone cannot carry them into these opportunities: we must continue to invest in the systems of work-finding and employment that work for women, at scale.

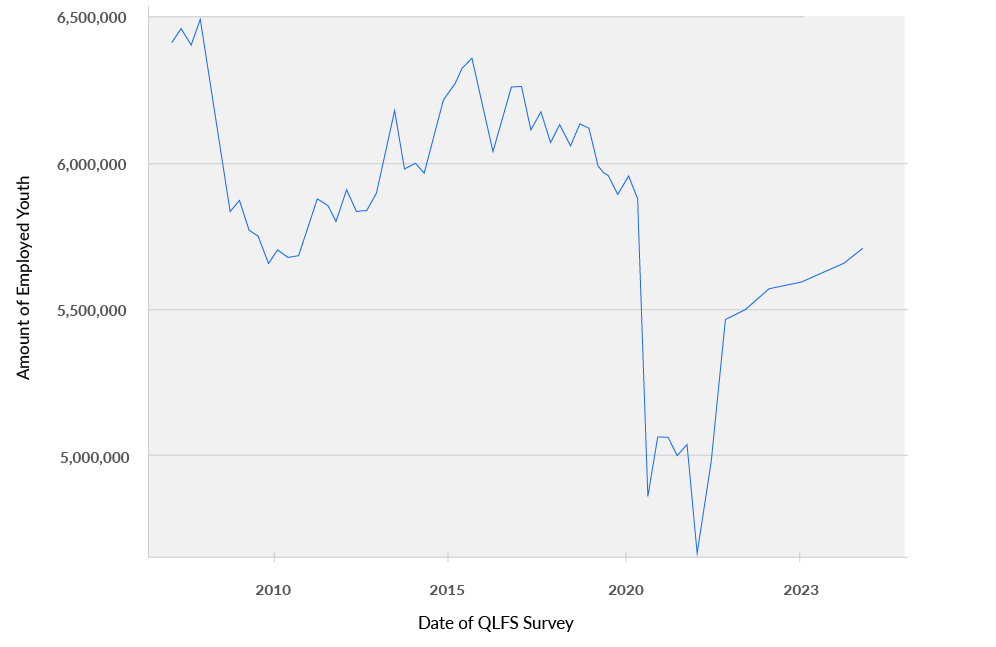

While overall employment rates appear to have returned to pre-Covid levels, the 18-34 age group still lags behind its pre-pandemic employment figures by approximately 250,000. This discrepancy gains significance when considering a larger time span: the second quarter of 2023 saw a notable decrease of 700,000 young workers compared to the same quarter 15 years prior, despite the growth of the youth population. Interestingly, female youth employment growth following the pandemic appears to have stalled, though male youth employment experienced some growth. Among NEETS (individuals not in employment, education, or training), for example, the rate for men decreased by 2,7%, but only by 0,3% for women. Another noteworthy trend is the continuous decline in the proportion of non-permanent youth jobs, indicative of a shift towards more precarious employment opportunities. This trend was briefly interrupted during the pandemic when many firms shed their non-permanent staff, but it has now recommenced. Compared to a year ago, the percentage of NEETS aged 15–34 years decreased by 1,5 percentage points from 45,0% to 43,4%. It is the total current count of 8.8 million NEETS, however, which underscores the alarming and ongoing challenges in the youth employment landscape.