SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

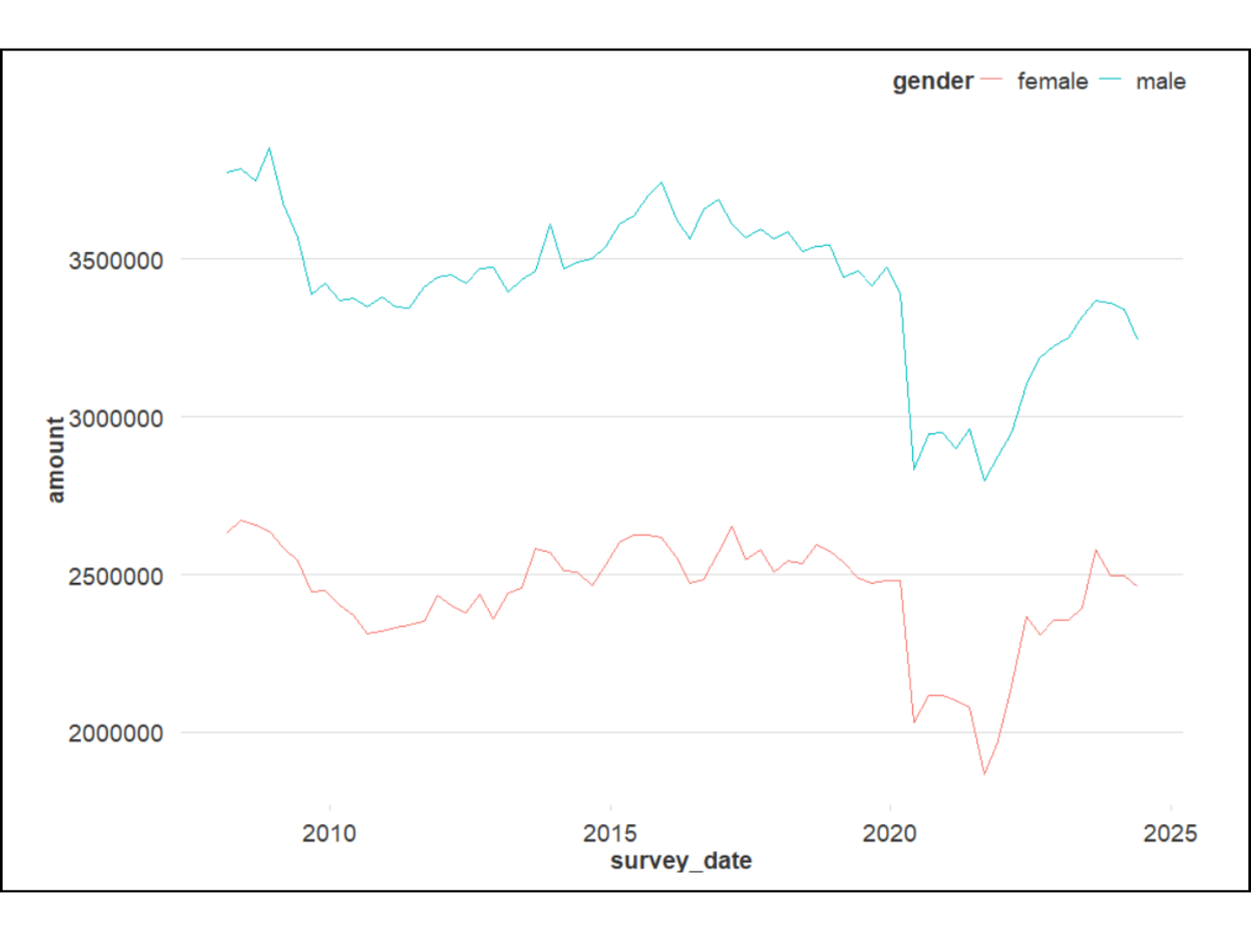

This August, we highlight the issues faced by young women in the South African labour market. Women’s struggles are evident in both the absolute and relative numbers: 2.5 million young women are employed compared to 3.3 million men, and the unemployment rate is 57% for young women versus 49% for men. Despite being more educated – young women are 10% more likely to pass matric, and 70% more likely to have a degree – they remain less employed, and experience higher barriers to labour market entry. Our data suggests that South African women, who represent 49% of the youth working age population and 47% of the youth labour market, are about 6.5 percentage points less likely to be employed, and also earn 6% less when they do find work. This translates into an earnings penalty of R3 240 per year for a starting salary of R4 500, or R129 600 over her lifetime – the cost of two years at a top university in South Africa, or nearly 10% of the down payment of an average house. Entering the labour market, for all youth, and particularly for young women, seems more difficult than ever. The average age of getting a first job has increased by 1 year for African women, and by smaller amounts for other demographics (QLFS 2014 – 2024). And even within the female demographic, some women are more excluded – women in metro areas with a matric are the most likely to find work, with those conversely, without a matric, or in non-metro areas, most likely to be unemployed. Spatial exclusion and education are some of the critical factors that impact one’s ability to access work and remain employed in South Africa.

Overall, women are less represented in the workforce. Even though they tend to be more educated, the proportion of young women in high skilled jobs is on par with men; women are much less represented in medium skilled jobs, and overrepresented in low skilled jobs. And when women do earn an income, there is a consistent gender penalty for the same work done – regardless of experience. Our data shows that women earn R173 less than men after transitioning to a 2nd job, which again translates into an earnings penalty of R83 040 over her lifetime. At the current rate of progress, it will take 102 years to close the gender gap in Sub-Saharan Africa (World Economic Forum, 2023).

All the data suggests that investing in women’s economic inclusion does not benefit women alone, but has an impact on society as a whole – for example, research indicates that women spend 90% of their income on families, in comparison to men’s 30-40% (UNAC, 2012). This is why disproportionate support for women’s access and inclusion matters – both for equity, and for its disproportionate impact on society. We need to be intentional about creating new jobs in opportunity zones for young women, and dismantling the existing barriers for women to access opportunities today. We also cannot forget the micro-economy of the household, where women’s work acts as both an unseen economic contribution, and if unrecognised, is the restraint that holds them back.

1 Statistics South Africa. (2024). Quarterly Labour Force Survey Quarter 1 2024.

2 Harambee calculations; earning estimate based in inflationary increases.

In this Breaking Barriers report, we have identified three levers for emphasis to address the barriers women face in the labour market:

Our Insight: Gender-specific language and incentives drive up women’s participation

Overall in South Africa, more women are employed in low-skilled work compared to men. The only sector where there is a higher proportion of women than men employed is the community, social, and personal services industry of which 65% of employees are female. In contrast, women are underrepresented in high and medium skilled occupations across other sectors, including financial intermediation, transport, trade, construction, utilities, manufacturing, mining, and agriculture. This has largely remained unchanged over time and remains despite women having higher educational outcomes in both secondary and tertiary education. We see this in the SA Youth data too – women are more likely to be employed in low-skilled jobs, and these low-skilled jobs pay, on average, 12% less than high-skilled jobs on the platform. Within low-skilled jobs on the SA Youth platform, women also, on average, earn R195 (or 9%) less than men.

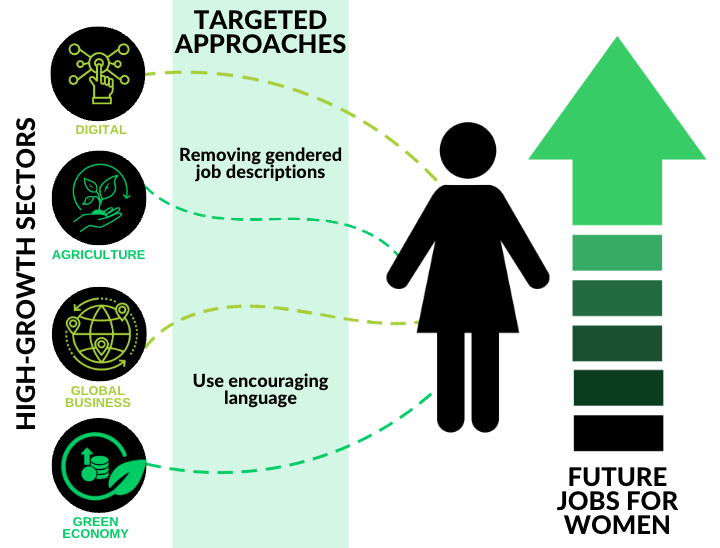

Overall these trends suggest that women are being squeezed from the medium-skilled work: this is work such as clerks, craft and service workers, agriculture workers and plant and machine operators. Many of these occupations could, with intentional targeted approaches, be performed by women. The medium skilled occupations that women are employed in are also occupations that are most threatened by automation and the rise of AI. Research from the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs report has shown that clerks are one of the fastest-declining roles, and this decline is driven largely by technology and automation. At the same time, female participation in STEM disciplines is considerably lower than their male counterparts. In South Africa, fewer than 13% of women choose to study a STEM discipline (Global Gender Gap Report) and globally women make up only 35% of STEM graduates – a number that has unchanged in the past 10 years.

But in contrast, the GBS sector is a great example of a high growth sector that has successfully prioritised the hiring of women. Compared to the ICT and digital sectors which comprise of only 22% and 17% female representation respectively, within the GBS sector women consistently make up 60 – 65% of new hires. This has been made possible with targeted incentive structures that drive up the hiring of women. With the signing of the GBS Masterplan and the anticipated job growth to 2030, we could see an additional 216 000 young women entering into decent employment through this sector.

And what of other sectors? A new report by Shortlist/BCG suggests that 1.5-3M new jobs in the green economy can be created across Africa, with nearly 300,000 in South Africa alone, and jobs in solar at 140,000. We have seen this first hand at Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator (Harambee) through our partnership with JP Morgan and Nepoworx to drive the inclusion of youth into solar panel installation. Through this, 120 participants are being trained and supported to become accredited solar installers – with 40% of the participants being female. A number of targeted approaches to ensure gender inclusion can drive up access. Shortlist’s research into gender gaps in the green economy also suggest that simply including language like “women are encouraged to apply” can increase female application rates. Removing gendered language from job descriptions, trimming down job requirements to only the most important qualifications etc. can encourage women to apply for roles. In fact, our President’s call to remove experience requirements is a positive step to ensuring inclusion – that, coupled with gender positive messaging, could drive up women’s application and entry into these roles.

Similarly, agriculture is a sector that holds promise for women – despite being laden with structural access issues. For example, globally, women make up nearly half of the agricultural workforce but hold a minor share of land ownership. In South Africa, cultural norms limit women’s land rights despite laws for equal tenure. Women’s land access is typically through family, inheritance, or marriage, not direct ownership. Systematic exclusion from programmes and financial support affects many women in agriculture, and women are often marginalised in decision-making, affecting policy relevance to their needs. The sector employs women mainly part-time or seasonally, while men hold more full-time roles. However, over the past 10 years, the agriculture sector has seen some of the highest growth in female youth participation, rising from 27.9% in 2014 to 32.26% in 2024, offering a beacon of hope. This not only reflects the potential for additional job creation but also offers secondary benefits from enhanced household food security and family livelihoods.

We know that targeting inclusion, intentionally, works. By pushing gender parity in sectors which traditionally have been under-represented by women, Harambee has seen higher proportions of females hired. This includes digital (65% of SA Youth placements are female), automotive (56% female), last mile service delivery (60% female), and utilities (60% female – in contrast to QLFS numbers indicating only 21% of workers are women). BluLever, a partner within the artisan sector is challenging assumptions around female representation, setting targets and achieving a 40% proportion against a sector average of around 13%. For BluLever, this inclusion “takes dedication and determination to create a space for young women in technical roles but young women have also repeatedly proven they are willing and able to match and in many cases outperform their male counterparts”.

3. Statistics South Africa. (2024). Quarterly Labour Force Survey Quarter 1 2024.

Our insight: Opportunities that offer mobility and flexibility uniquely address gender barriers

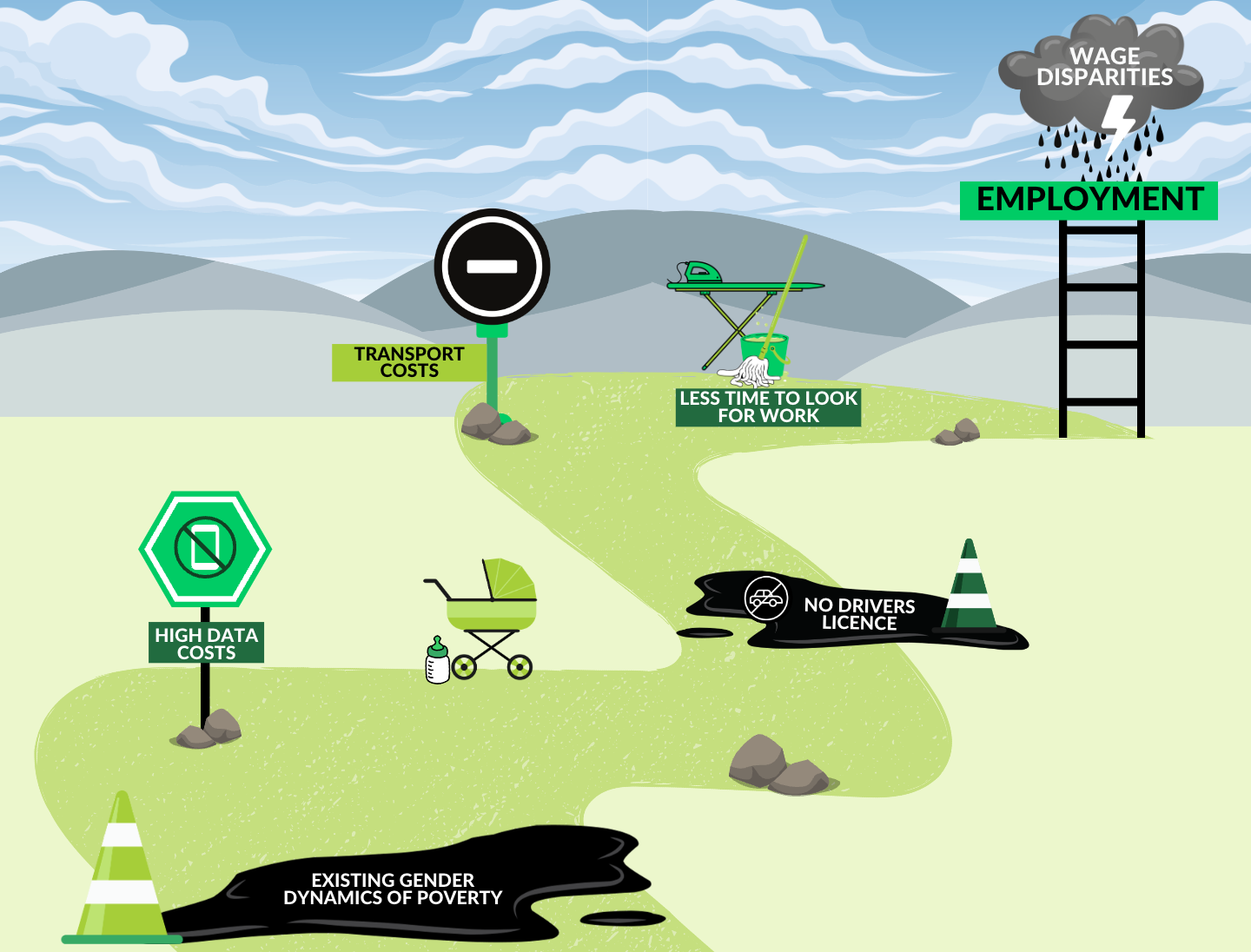

Two of the most significant demographic factors impacting ability to find employment in South Africa are proximity to jobs and level of education. Restrictions on physical mobility limit women’s access to better-quality and higher-paid jobs, their ability to navigate and claim public spaces, and hinder their participation in essential activities such as acquiring an education, engaging with a larger community, and accessing healthcare. And we see this in our data. Women with a matric in a metro area are least likely to be unemployed – whereas the penalties for not having a matric and then living in a non-metro area, are dire. Barriers for those without matric and in non-metros are compounded by few job opportunities, and limited digital literacy and online access.

While SA Youth’s online platform alone may be insufficient to support these cohorts, a more holistic ecosystem approach is needed. Harambee’s experience has shown that providing matric-qualified women in non-metro areas with opportunities – whether through public employment or informal work opportunities, can have a significant impact on labour market access. Illustrating this market access, 17% of youth jobs nationally go to young women with matric outside the metros, but 30% of reported placements on SA Youth are from this cohort.

On the SA Youth platform, 71% of individuals linked to opportunities for self-generated income over the last financial year were young women. However, engagements with female business owners in our network indicate that the challenges young women face are unique, and the gender income gap for these opportunities remains high. Providing a service provides 1.3 times more income than selling a good, however more men are able to provide services due to women being bound by unequal home and care duties. Further, specific barriers include male customers doubting the quality of their services and subjecting women to unwanted harassment. Harambee seeks to give women a leg up by highlighting the unique challenges they face through our female-led content offerings on our SA Youth platform, while also specifically targeting excluded women through our pilot programmes, thereby empowering them to earn dignified and safe incomes.

One of our partners that provides flexible opportunities disproportionately for women is Gobuddy, a platform creating sustainable earning opportunities in the last mile delivery sector for excluded youth while also reducing delivery costs for their customers. Gobuddy connects people to the eCommerce industry, offering them the opportunity to deliver goods and earn by matching their daily travel routes to deliveries travelling in the same direction. In the few short months of operation, the model has shown to be gender inclusive with 60% of individuals transporting goods being female. Whilst not specifically targeting women in their model, Gobuddy have found that these opportunities are appealing because it enables women to generate an income at a time that is convenient to them, without having to sacrifice other roles such as a caregiver. The impact of leveraging the existing transport routes of individuals also provides significant green benefits, with a total travel saving of 14 287 km and CO2 emission saving of 1 738kg for the environment.

Finally, directly subsidising transport itself can have a huge dent on gender inclusion. In India, for example, the Karnataka Government’s Shakti Scheme addressed this barrier head on, by offering fare-free rides on state buses for women, aiming to improve access to education and employment by reducing mobility barriers. Launched in June 2023, the scheme saw 167 million free trips in the first month, with an average of 5.5 million women travelling daily. In five months, one billion free rides were taken, saving women between INR 1,000 – 1,326 (R220 – R300), which they redirected towards family needs. The scheme also supports youth in attending job interviews, reducing their transport costs. In South Africa, by supporting youth with transport options to attend job interviews, we can similarly defray transport costs which stand at R700 per month for the average work-seeker, and more than a third of wage income for those who work and have lower earnings. Harambee is currently exploring opportunities with large ride-hailing companies to assess how transport vouchers and support can address this major barrier.

4 Statistics South Africa. (2024). Quarterly Labour Force Survey Quarter 1 2024.

Our insight: ECD is needed everywhere in South Africa and demand for it is growing. Formalisation approaches must serve this demand, not curb it.

Unpaid care work disproportionately affects women’s participation in the formal labour market, leading to occupational segregation and lower-paid positions. Women often opt for part-time or informal jobs due to caregiving needs, limiting access to higher-status roles and contributing to the gender wage gap. Although unpaid care work is economically significant, it’s often unreported and not recognised in public policy, rendering women’s contributions ‘invisible’ in economic measures.

Within South Africa, it is estimated that the care economy contributes 13.8% towards total employment, most of which is undertaken by women. Women who do manage to enter the labour market face the additional hardship of time poverty – a consequence of the ‘double load’ of women’s paid work responsibilities combined with their domestic and family responsibilities and unpaid care work. QLFS data reveals that women carry the brunt of unpaid care responsibilities – 750 000 young women indicate they are not economically active due to being a homemaker, which is 5 times the comparable number for men. This is also a loss of potential and productivity to the economy and our society.

The Early Childhood Development (ECD) sector provides a triple impact opportunity for economies: a source of employment, the provision of physical, socio-emotional and early learning input for children, and support for primary caregivers to access childcare and reduce this time poverty. There remains a growing need for ECD care – with the 2030 ECD Strategy aiming to reach 1.2 million additional children in need of quality care over the next 5 years. If addressed, 270,000 direct jobs could be generated and up to half a million women and caregivers enabled to re-enter the labour market.

And yet, despite this growing need, many ECD providers struggle to access existing budgeted subsidies to scale and grow. With only 40% of ECD centres being registered, and 33% receiving the government’s ECD subsidy, formalisation within the ECD sector has traditionally been associated with high costs, bureaucratic processes, misinformation and geographic inconsistencies. Efforts however are being made to reduce the barriers to ECD registration and enable the flow of funds to create sustainability and expand access. Work is being done within the Red Tape Reduction Unit to review the municipal requirements of the ECD registration process, identifying innovations across municipalities that can be adopted.

In July 2024, the Department of Basic Education (DBE) launched the ECD Mass Registration Drive with the objective to register 20,000 Early Learning Programmes (ELPs) in South Africa over the next 18 months, streamlining the process for ELP owners to achieve regulatory compliance whilst ensuring quality standards. Harambee’s contact centre provides operational support for ECD registration through our phone and WhatsApp channels. The initiative, piloted in Johannesburg South so far, has already reached over 400 ECD practitioners, enabling the application of 221 ELPs, and formally registering 62 to bronze status – all within the first month. This is already 20% of all new ECD centres registered in Gauteng last year. A critical enabler to the mass registration model is partnership with local NGOs, who have a track record of supporting ECD centres on the ground. By utilising their networks, the campaign can obtain both the buy-in and reach required for scale to other provinces from September 2024. By leveraging systems, processes and sector partners, formalisation of ELPs can be inclusive and respond to the needs and realities of ECD practitioners.

Formalisation of ECD centres also provides a blessing in the form of access to the ECD subsidy for low income households. Estimated at a maximum of R4 488 per child per annum, the subsidy alone is insufficient to cover all costs experienced within an ELP. However, the provision of this public funding is catalytic in easing the financial burden of ECD access. Through the ECD Mass Registration campaign, an additional R700 million of public funding could be unlocked in the next year through new ELP registration. With 2030 plans by the DBE to both increase the amount of the subsidy to cover 65% of ECD costs and to treble the expanded reach of the subsidy, this would channel a total of R18.93 billion in public funding through the ECD subsidy – making early learning more affordable.

Winning the war on the gender gap requires targeted interventions to promote gender inclusion in the jobs of tomorrow; dismantling specific barriers to inclusion for jobs of today, and rendering the care economy visible. There are no highways out of exclusion and poverty, particularly for women. The work ahead is painstaking but has to be intentionally inclusive. In particular, while waiting for the economy to move, we need to unlock opportunities closer to – and even within – home, to have them intentionally support women. We all stand to benefit as a result.

5 Youth Capital (2023). Beyond the Cost Report.

6 The Growth Lab (2023). Growth Through Inclusion in South Africa.

The latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey results continue to reflect the dire state of youth employment, particularly amongst young women. For the broad population, employment has decreased by 92 000 in the past quarter, with both the official and expanded unemployment rates increasing to 33,5% and 42.6% respectively in Q2. This overall drop is made up of a 43 000 increase in employment for those over 35, offset by a 135 000 decrease in youth employment. This tendency of our economy to provide growth in jobs for experienced workers at the expense of youth jobs has persisted for as long as Stats SA has been tracking this level of data, and points to deep rooted barriers to youth employment compared to non-youth. Youth employment still hovers below 6 million people, a number lower than the one recorded in 2008. In contrast, employment of non-youth (those above 35) increased from 8 million to 11 million over that same time period. We are leaving our young people behind.

This quarter’s drop can potentially be attributed to the seasonal drop in employment often experienced in April but it is also estimated that the General Election contributed to business reticence around hiring. The informal sector grew by 48 000 jobs, and within the formal sector (which contributes 68.9% of total employment), the largest employment gains were recorded in manufacturing and community and social services. Employment losses were experienced in trade, agriculture and private households.

Amongst youth aged 18-34 years, the youth unemployment rate reached 55.8%, up from 54.4% last quarter. The decline in employment was experienced more heavily amongst young men, who have been impacted by the number of physical-related jobs that have vanished since the pandemic. There is also a broader trend relating to the ongoing fall in permanent jobs since 2020, which is reflected in the overarching reduced employment figures and is characteristic of a labour market in churn. As a result, the number of youth NEETs has surpassed 9 million with 51% of young people aged 18-34 years not in employment, education or training.

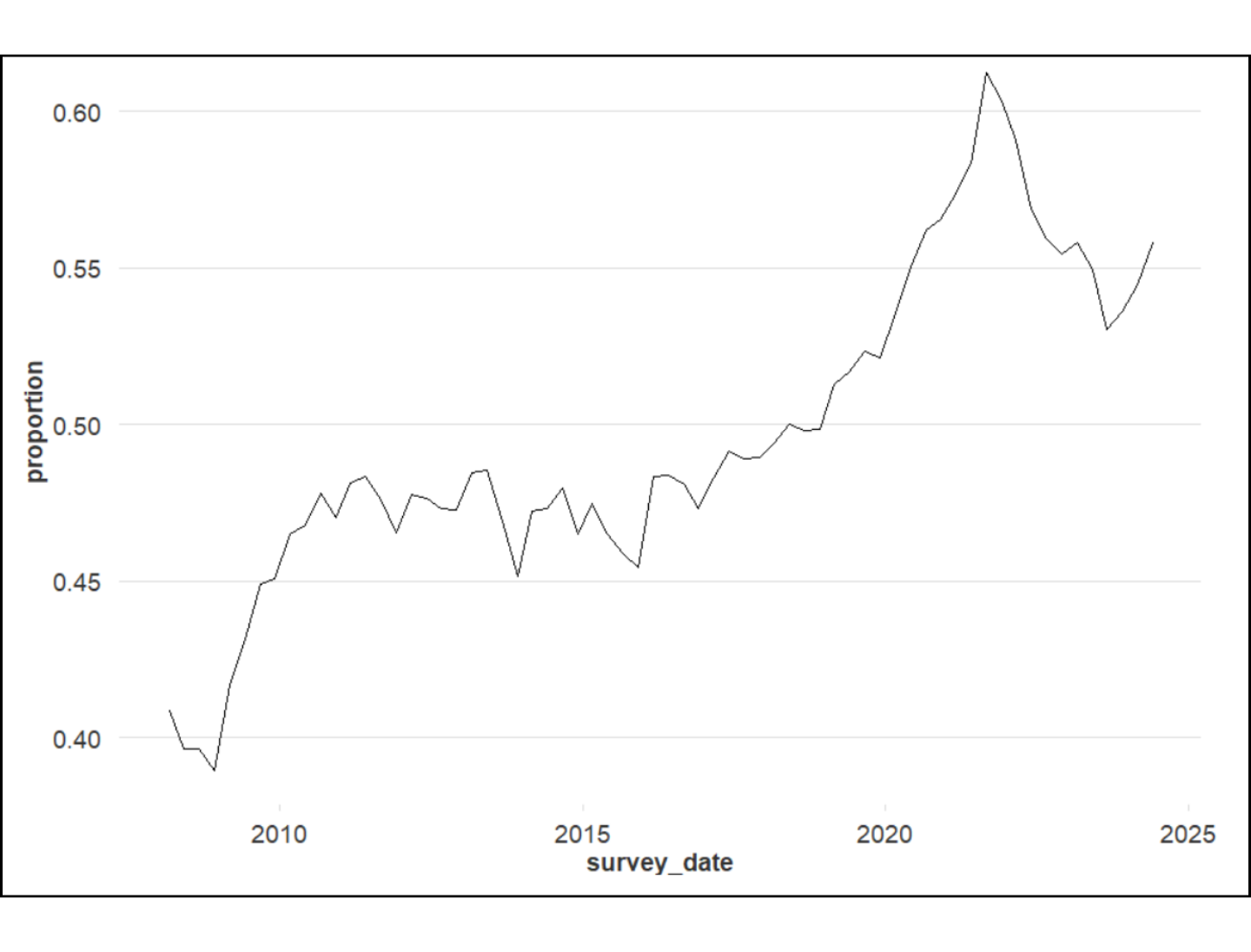

The gender penalty that women face is showcased in the data. Women experience lower levels of employment (7.4 million vs. 9.2 million men), lower labour absorption rates (9.1 percentage points difference), and a consistently higher unemployment rate (35.8%) – above the national benchmark. Critically, the number of women not economically active is 30% more than men, often driven by unpaid care work. Much still needs to be done to reduce the barriers young women face to enter, retain and thrive within the labour market but their perseverance is evident. Over the past 10 years, the labour force participation rate for women has increased by 5 percentage points highlighting a generation of women that are ready and willing to work.

Expanded Youth Unemployment Rate

Youth Employment by Gender